About the Post:

Owing to my passion for history, archaeology, anthropology, etymology, and the like, at times I make some strange observations; I would like to share with you one such peculiar perception in this post. This post is all about a few surprising similarities between two distinct geographical locations—the Kutch region of Gujarat (an Indian state), and the Kachcha-theevu (an island in the Indian Ocean) surroundings.

Disclaimer:

I don’t read many books or articles, and hence I am not aware if someone else has already written about the same/similar topic; in case anyone has done so, I owe due credit to them. Moreover, since Kachcha-theevu (ceded to Sri Lanka in 1947 by India), alias Vali-theevu, has become a sensitive issue nowadays, I would like to deliberately declare that this article has nothing to do with politics.

Sneak Peek:

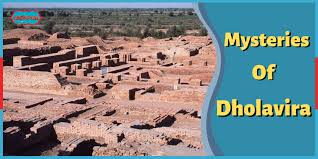

Could the present-day Harappan site of Dholavira be the remains of the Dvaraka city mentioned in the Mahabharata?

Continue reading to trace the truth ………..

The Similarities:

The names of certain places and rivers in the Kutch region of Gujarat resemble the names of certain places located in the vicinity of the maritime boundary which separates the maritime zone of India from that of Sri Lanka.

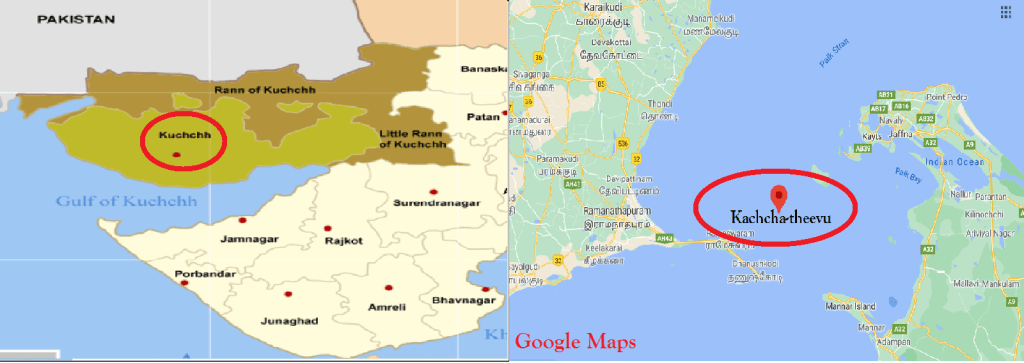

Kachchh and the Kachcha:

At the outset, the name ‘Kutch’ (also spelt as Kachchh/Kuchchh/Cutch) itself sounds akin to the name ‘Kachcha-theevu’. Since ‘theevu’ is the Tamil equivalent of the English word ‘island’, we infer ‘Kachcha’ as the actual name of the island. It is needless to say that the ‘Kachcha’ (island) of Sri Lanka sounds and spells similar to the ‘Kutch’/’Kachchh’ (district) of Gujarat, in India.

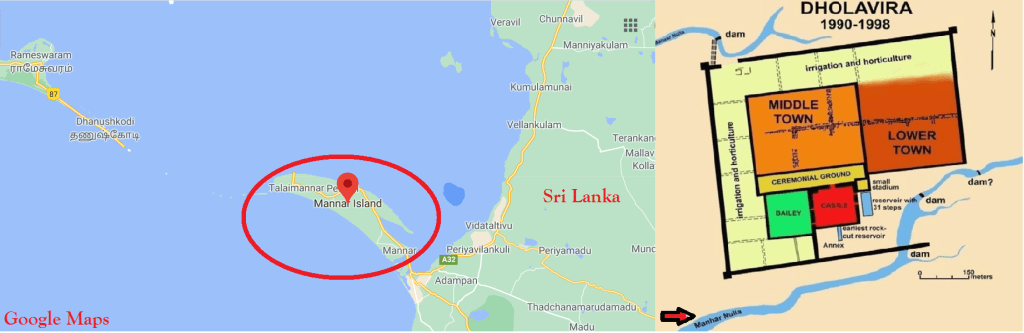

Manhar and the Mannar:

‘Manhar’ is one of the two seasonal streams which quenched the thirst of Dholavira, a Harappan town of the ancient past, located in the Kutch region of Gujarat. One can notice that this ‘Manhar’ is comparable with the name ‘Mannar’ (‘Mannār’) of an important town in the northernmost part of Sri Lanka, owing to which the Gulf of Mannar got its name. The prominence of ‘Mannar’ is demonstrated in the names ‘Mannar’ District (to which the Mannar town belongs), Mannar island (where the Mannar town is situated), and the Talai-Mannar settlement of Sri Lanka.

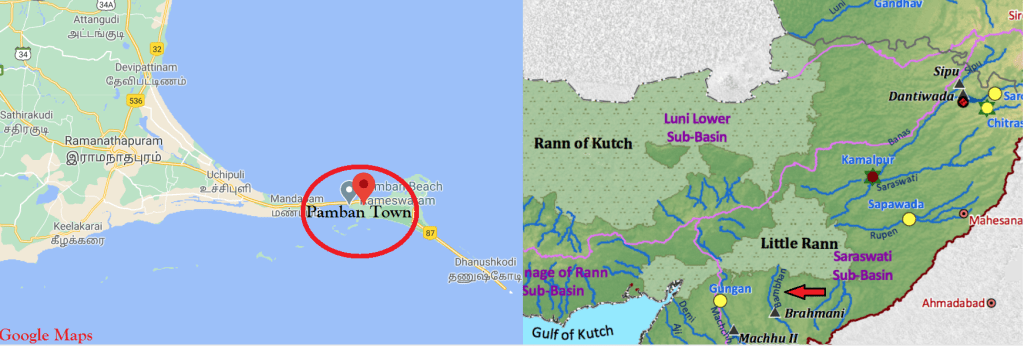

Bambhan and the Pamban:

‘Pamban’ (‘Pāmban’) is a prestigious island belonging to India, where the most adored pilgrimage town of Rameshwaram (‘Rāmēshwaram’) is situated; hence it is also known as ‘Rameshwaram Island’. The Pamban Island (in India) lies more or less straight in line with the Mannar Island (in Sri Lanka); both these islands, together with the shoals of Rām-Sethu/Adam’s bridge separate the Gulf of Mannar from the Palk Bay. Obviously, the Pamban Island owes its name to the major town called ‘Pamban’, which comes under the Rameshwaram ‘taluk’ (an administrative division), which in turn belongs to the Ramanathapuram district of Tamil Nadu, in southern India. Coincidentally, there is a lesser-known river called ‘Bambhan’ (probably pronounced as ‘Bāmbhan’) that flows into the Little Rann of Kutch, which itself is a part of ‘Rann of Kutch’ – a huge area of salt marshes, largely located in the Kutch District of Gujarat.

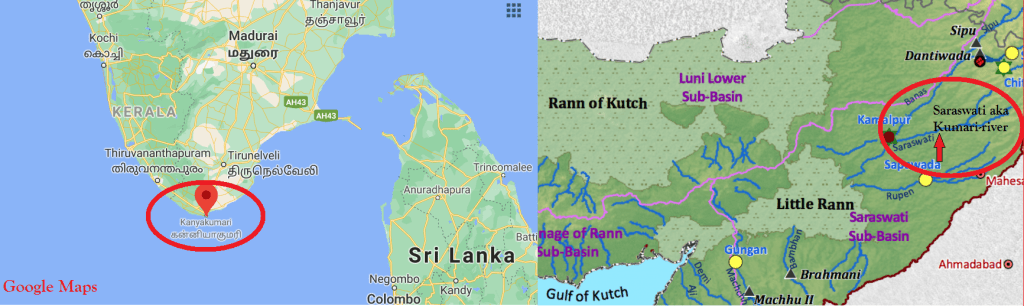

Kumari and the Kanya-Kumari:

In ‘The Lost River’ authored by Michel Danino, one can find (on Page No. 49) the information about a river that bears the name ‘Saraswati’ alias ‘Kumari’. This is definitely not the ancient majestic River Sarasvati that once flowed through the deserts of Rajasthan (India) and Cholistan (Pakistan); this is but another small river that has its source at the south-western tip of Aravalli Hills. This Saraswati’s full course runs for hardly a distance of 200 km to join the Little Rann of Kutch; as it does not ‘mingle’ with the ocean, it is also known as ‘Kumari’ (meaning ‘virgin’). Now, when we travel down to the south again on our journey of spotting the perplexing parallelisms between the Kutch region and the Kachcha-theevu surroundings, we have this holy town called ‘Kanyā-Kumari’ (spelt without diacritics as ‘Kanya-Kumari’) at the southernmost tip of peninsular India, which is generally referred to as ‘Kumari’, especially in Tamil literature. It is the native deity ‘Devi Kanyā-Kumari’ (goddess ‘Shree Bhagavathy’ in the form of a ‘virgin girl’) who has bestowed her name to the town as well as the district which houses the town of Kanya-Kumari. Moreover, there is a popular belief that there was a river named ‘Kumari’ in a now-submerged landmass that once existed just below the present-day Kanya-Kumari.

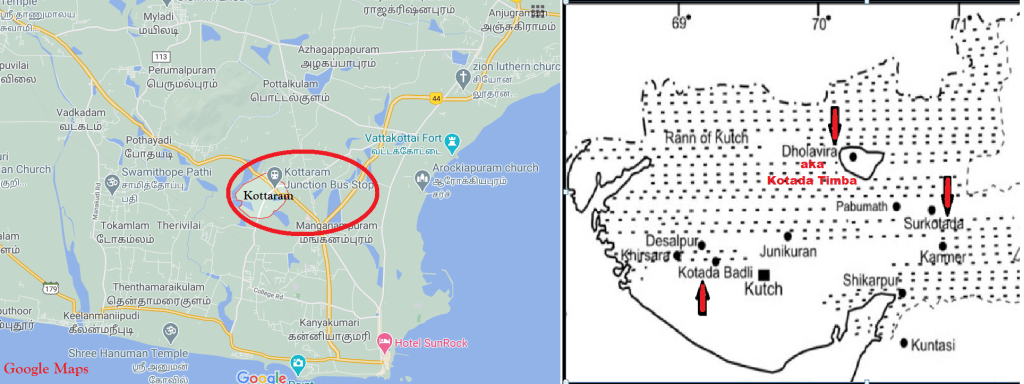

Kotada and the Kottaram:

Among the various Harappan sites of Gujarat, three unique sites in the Kutch District are Surkotada, Kotada-Timba (local name of the Dholavira), and Kotada-Bhadli; perhaps there are many more ‘Kotadas’ in Gujarat. Based on the Tamil word ‘கோட்டை’ (‘kōttai’) which means ‘Fortress’, I guessed that the word ‘Kotada’ might be the native (Gujarati) word for ‘Fort’; thanks to my friend who confirmed (by referring to the Gujarat tourism website) that ‘Kotada’ indeed means ‘large fort’. In fact, archaeological remains of fortification walls are found at each of these three excavated Harappan sites. To complete the list of similarities discussed in this post, we have a village named ‘Kottaram’ (‘Kottāram’) in the Kanya-Kumari district of Tamil Nadu. ‘Wikipedia’ states that the village was ruled by Travancore ‘Mahārājas’ (kings of Thiruvananthapuram) during the 18th and early 19th centuries and hence the village got the name ‘Kottāram’, which means ‘palace’ in the Malayalam language. It could very well be so but still, I would like to notify you here that although ‘அரண்மனை’ (‘araNmanai’) is the commonly used Tamil word to denote a royal palace, one can actually find ‘palace’ as the English translation of the Tamil word ‘kottāram’ (‘கொட்டாரம்’) in Tamil to English dictionaries. I believe that, in the Indian sense, a king’s ‘palace’ always meant a fortress or a mansion within a citadel complex. I derive this notion from the fact that excavations at almost every major Harappan site have so far exposed fortification walls but no signs of extravagantly luxurious palaces. My conception gets further strengthened by the anatomy of the Tamil word ‘அரண்மனை’ (usually translated as ‘palace’), in which ‘அரண்’ means ‘fort’/’castle’ and ‘மனை’ means ‘house’/’plot’. When all is said and done, we realize that the Gujarati ‘kotada’ is analogous to the Tamil/Malayalam ‘kottaram’ in terms of implication (meaning) and phonetics (sound). Thus there is a chance that ‘kotada’ is a modification of ‘kottāram’, especially because the sound ‘ra’ is pronounced as ‘da’ in certain Hindi words (and perhaps in Gujarati too).

Relevant References:

I am indeed aware of two fragments of information from the Sangam/ancient-Tamil-Literature, which in my opinion can be sensibly associated with this topic; hence I feel obliged to narrate the same here.

The story of the southern migration of people from ancient Dvārakā, under the leadership of Sage Agastya, is narrated by the Tamil scholar Nacchinārkkiniyar (circa 6th or 7th century CE) in his commentary on Tolkāppiyam (pāyiram; Porul. 34)—the earliest available work of Tamil literature. According to this legend, Sage Agastya led eighteen families of ‘Vēlir’ and ‘Aruvālar’ clans along with eighteen ‘Vēndars’ (kings) from ‘Tuvarai’ (Dvārakā) to the south, where they got settled clearing the forests and cultivating the lands.

In Puranānooru (poem no. 201), the famous Tamil poet Kapilar of the Sangam Period (circa 50–125 CE), during his attempt of persuading King Irunkōvēl (a Vēlir king) to marry the two daughters of Vēl Pāri (another famous Vēlir king), mentions Irunkōvēl as the 49th king in the lineage of his ancestors (Vēlir kings) who had migrated from ancient Dvārakā to the south.

Closing Message:

The above two stories seem to aptly fit into the context thereby solving our jigsaw puzzle, but it has to be remembered that unless we possess undeniable evidence(s) in support of this theory, we cannot relate these stories to the stunning similarities analyzed in this post. It is true that the ancient city of Dvārakā (capital of ancient ‘Anarta’ Kingdom) existed not too far from the Kutch region of present-day Gujarat; still, we neither know whether the Kutch region was a part of ancient Dvārakā or Anarta nor do we know if the Kutch land was inhabited by the Vēlirs and/or the Aruvālars during the ancient past. Hence, I wish to keep this matter open to healthy discussions, so that I get a chance to learn the perspectives of others which will be of great use to amateurs like me in tracing the unknown history of our sub-continent. By the way, I request those who are interested in Ramayana to check out my next post.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for an introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Click Contact to send me a message or to find me on social media.

Interestingly, the word Kutch as used in Gujarat or as in Kacchabareswarar temple in Kanchipuram, denote “Tortoise”.

Kutch means that which is alternately dry and wet (Rann of Kutch) and also as to analogously mean the amphibious tortoise.

In the area of Kacchabareswarar temple, it is said that Lord Vishnu worshipped Lord Shiva to assume the form of a tortoise to assist in the churning of the ocean. In the same village as the Kacchabareswarar temple is the Marundeeswarar temple (eponymous with the one in Thiruvanmiyur).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting sharing. Thank you

LikeLike

Correction to above comment – it is Kachabeswarar, not Kachabareswarar

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot for your informative Comments. Kindly continue to visit my blog for newer posts. Thank you 😊

LikeLike

Excellent compilation

LikeLike