About the Post:

Mahabharata cannot be branded as mere mythology anymore; the authenticity of the epic has been established to a notable extent by the discovery of submerged Dvaraka and the archaeological excavations conducted at various Mahabharata sites. However, scholars differ in their opinion when it comes to dating the epic. This post is all about detecting the date of Mahabharata’s core story, with the help of the epic’s own content and the corresponding archaeological facts.

Disclaimer:

I am not aware if someone else has already worked on this subject in a manner similar to that of mine; in case anyone has done so, I owe due credits to them.

Sneak Peek:

While the Pandavas and the Kauravas were preparing for the Kurukshetra War, Lord Krishna’s brother Balarama decided to go on a pilgrimage along the holy river Sarasvati.

Want to know how Balarama’s pilgrimage is useful in deducing Mahabharata’s age? Just follow his trail to find the answer………….

Krishna and His Dvaraka:

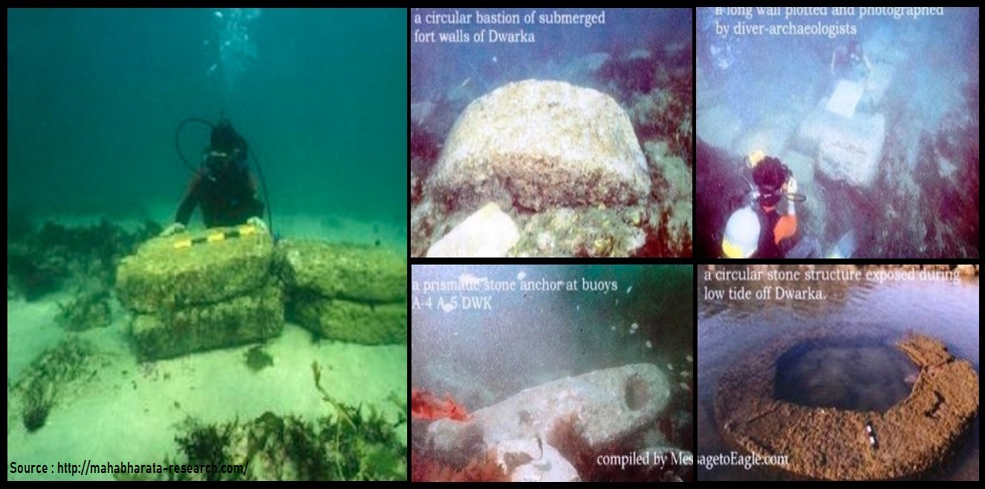

Lord Krishna is a deified personality in the sacred epic Mahabharata. The epic states that Krishna founded the city of Dvaraka in the western region of ancient India (present-day Gujarat, India), by reclaiming a piece of land from the sea (now known as the Arabian Sea). Mahabharata also declares that the grand city of Dvaraka eventually got submerged in the sea, when Krishna left his mortal frame.

The Traditional Date:

Aryabhatiya(m) was a book authored by Aryabhata (476–550 CE/AD) who was an Indian astronomer and a mathematician. He has mentioned in his book that the same was written by him in the 3600th year of Kali-yuga when he was 23 years of age. Given that Aryabhata was born in 476 CE/AD, the beginning of Kali-yuga would come to 3102 BCE. Moreover, it is said that the Surya-Siddhanta indicates the commencement of Kali-yuga at midnight (00:00) of 17th-18th February 3102 BCE. According to Puranic sources, Krishna had crossed 100 years of age well before his departure from this mortal world and the end of Krishna’s incarnation marked the birth of Kali-yuga; thus it is inferred that Krishna lived from circa 3250 to 3100 BCE, that is approximately 5000 years before present.

The Scientific Date:

The submerged Dvaraka was discovered under the waters of the Arabian Sea during the 20th century CE/AD by Dr.S.R.Rao (1922–2013), who was an Indian archaeologist and the pioneer of Marine Archaeology in India. Based on the material evidence and the Thermo Luminescence [TL] dating results, Dr.S.R.Rao concluded that Lord Krishna and his Dvaraka existed during circa 1700–1500 BCE (a Late Harappan period).

Science Vs Tradition:

The matter is not as simple as it looks because there are at least a dozen of differing conventional as well as scientific dates—ranging from about 1000 BCE to 5500 BCE—proposed by scholars and researchers of various academic disciplines; out of them, I have quoted only the comparatively reliable ones. All said and done, the scientific date of ancient Dvaraka evidently contradicts the orthodox date (circa 3102 BCE) of the same. At this point, I would like to quote the following statement from Dr.S.R.Rao’s book—’THE LOST CITY OF DVĀRAKĀ—’in which the abbreviation ‘BDK’ refers to ‘Bet-Dwaraka’, an Island near the present-day town of Dwaraka in Gujarat, which is an important archaeological site associated with ancient Dvaraka:

“Although the traditional date 3102–1 BC. cannot be confirmed by the available archaeological evidence, it is better to explore deeper waters of BDK”

I have immense regard for Dr. S.R. Rao and his tremendous work; nonetheless, I personally accredit the traditional convictions passed on to us through generations, by our ancestors. Hence I did not give up my search for the scientific data that would testify to the traditional date.

The ‘Eureka’ Moment:

I happened to read the book ‘THE LOST RIVER – On the trail of the SARASVATI̅’, authored by Michel Danino, which is a treasure trove of scientific facts about River Sarasvati. The crux of Danino’s book seemed much relevant to the episode of Balarama’s pilgrimage, narrated in the Shalya Parva (a section) of Mahabharata; the set of three maps of reconstruction of Sarasvati basin’s hydrography – proposed by Danino – promised key clues to determine Mahabharata’s date.

The Providential Pilgrimage:

When both Pandavas and Kauravas approached Krishna, seeking his alliance prior to the ‘Great War of Mahabharata’, Krishna promised personal help to the Pandavas and military support to the Kauravas. However Balarama (Krishna’s elder brother) decided not to take part in the war and hence, as a pretext, he undertook a pilgrimage to the holy tirthas (sacred sites associated with water bodies) along the now-defunct River Sarasvati.

According to ‘The Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa‘ – translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli – Balarama, who started his pilgrimage from Dvaraka with his paraphernalia (consisting of priests, Brahmins, friends, servants, cars, elephants, steeds and many vehicles drawn by kine and mules and camels), first proceeded to the holy tirtha named Prabhasa (in present-day Gujarat, India). From there he traveled upstream to reach Chamsodbheda, where he and his pilgrimage party passed the night. Then the party moved further to reach Udapana where River Sarasvati was invisibly flowing underground. After bathing in the sacred waters of Sarasvati at Udapana, Balarama traveled to Vinasana – the place at which Sarasvati had become invisible by forsaking her flow above the earth’s surface. Balarama bathed in the waters of Sarasvati at Vinasana and then moved on to Subhumika, from where he proceeded to the tirtha of Gandharvas and then to the sacred tirtha called Gargasrota; he continued to travel further visiting several holy tirthas on the banks of Sarasvati. Balarama thus commenced his pilgrimage from the southern banks of Sarasvati and continued his journey upstream thereby worshiping several sacred spots along the river’s course until he finally reached Kurukshetra which, according to Mahabharata, was a sacred plain region (vaster than the present-day Kurukshetra town in India) sandwiched between the divine waters of River Sarasvati (in the north) and River Drishadvati (in the south); Kurukshetra of Mahabharata times was located just above the confluence of these two holy rivers.

Interpreting the Information:

Mahabharata explicitly mentions that Balarama bathed in the holy waters of Sarasvati at every tirtha and gave away several gifts to the pious Brahmins dwelling at the various tirthas visited by him. This valuable information confirms that the river bed of Sarasvati was definitely not bone-dry during the Mahabharata days; indeed it bore sufficient water, either above or below the surface of the earth, to support the orthodox Brahmin settlements almost all along her lengthy course. Thus Balarama’s pilgrimage episode gives us an overall picture of River Sarasvati’s status during the Mahabharata period, as follows:

[1] River Sarasvati was quite a functional river system during the Mahabharata days; this is evident from the fact that Balarama, during his pilgrimage, repeatedly ‘applauded’ River Sarasvati and visited several Brahmins (rather Brahmin communities) ‘living’ on her banks.

[2] River Sarasvati disappeared at a place called Vinasana; Michel Danino’s ‘The Lost River’ quotes that Pan̅chavimsha-Brāhmana (an ancient Hindu text) locates Vinasana below the Sarasvati-Drishadvati confluence.

[3] Sarasvati’s visible flow was absent at a place called Udapana but her subterranean flow at the spot was evident; Mahabharata adds that the herbs and the ascetics of the land were witnesses to her ‘invisible current’.

[4] Sarasvati plausibly reappeared as quite a prominent river at Chamsodbheda; this notion is an assumption from the fact that Balarama, with his huge paraphernalia, spent the whole first night of his pilgrimage trip at Chamsodbheda. Moreover, Vana Parva of Mahabharata confirms that Sarasvati disappeared at Vinashana and re-appeared at Chamsodbheda. In addition to these details found in Mahabharata, Wikipedia states “according to the Mahabharata, the 4,925 kilometers (3,060 mi) long Sarasvati River dried up to a desert (at a place named Vinasana or Adarsana) and joins the sea impetuously“.

The Sarasvati Saga:

Sarasvati is one of the seven significant rivers in the Rig Veda; later-Vedic and post-Vedic texts also mention the river. The Nadistuti-Sukta in the Rigveda (10.75) locates River Sarasvati between the Yamuna in the east and the Sutlej in the west. Skanda Purana says that Sarasvati originates in the Himalayas and then turns west at Kedara and also flows underground. Rigveda (7.95.1-2) describes Sarasvati as a river flowing to the samudra (translated as “ocean”/”lake”). The Mahabharata as well as the later-Vedic texts like the Tandya and Jaiminiya Brahmanas declare that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert. Rigvedic and later-Vedic texts have been used to propose the identification of Sarasvati with present-day rivers or ancient riverbeds.

Sarasvati in Current Era:

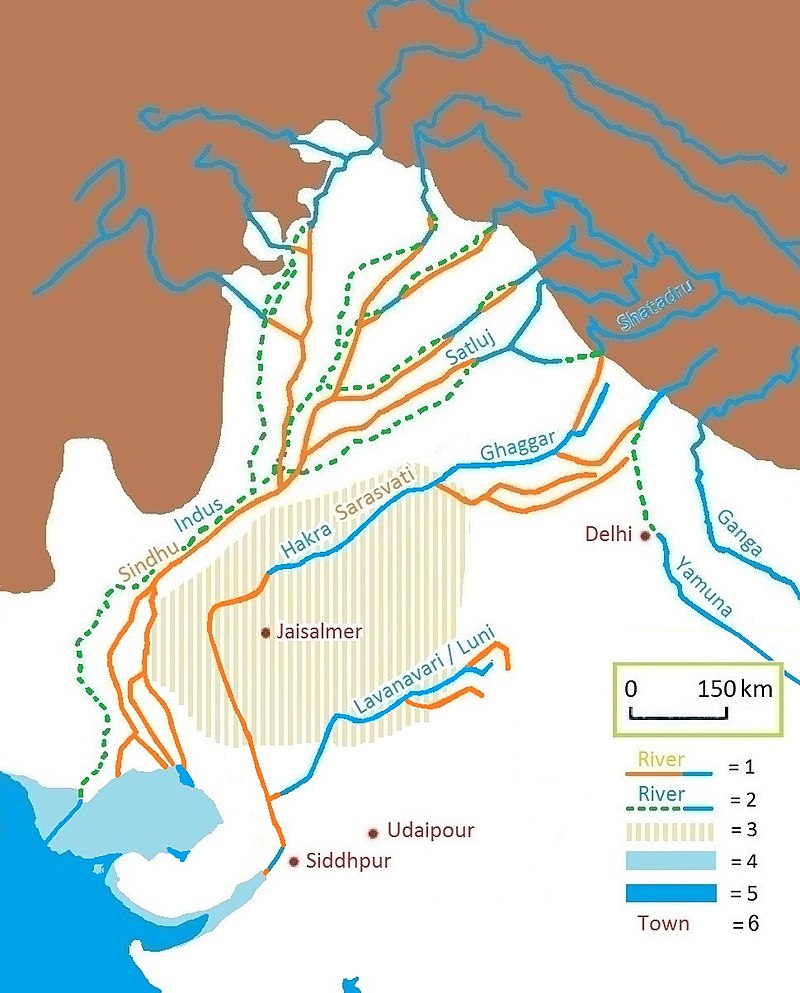

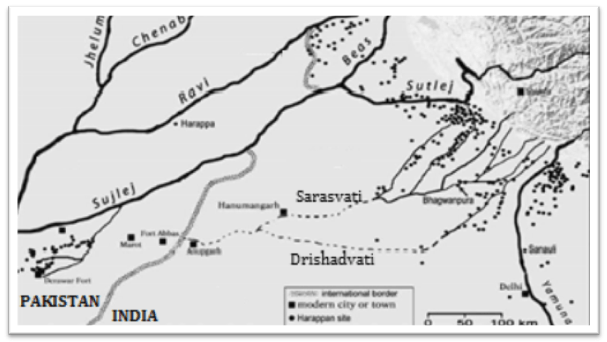

Michel Danino’s ‘THE LOST RIVER’ reveals that the scholars of modern times have identified present-day River Ghaggar-Hakra as the archaeological remains of ancient river Sarasvati. Ghaggar is a seasonal river in India, flowing during the monsoon rains; originating in the Shivalik hills of Himachal Pradesh, Ghaggar flows through Haryana (during good monsoons) and continues its course (rather a dry course) through Punjab and northern Rajasthan. Hakra is the Pakistani counterpart of Ghaggar; starting as the continuation of Ghaggar near Fort Abbas city in the Cholistan Desert of Pakistan, Hakra’s dried-out course traverses all the way to Rann of Kutch through the Sindh province of Pakistan. Numerous archaeological remains of riparian Harappan settlements have been discovered along the course of Ghaggar-Hakra; based on the distribution pattern of these sites, Michel Danino has charted out a set of three maps, proposing the reconstruction of the Sarasvati basin’s hydrography during the Early, Mature and Late Harappan phases.

The Three Maps:

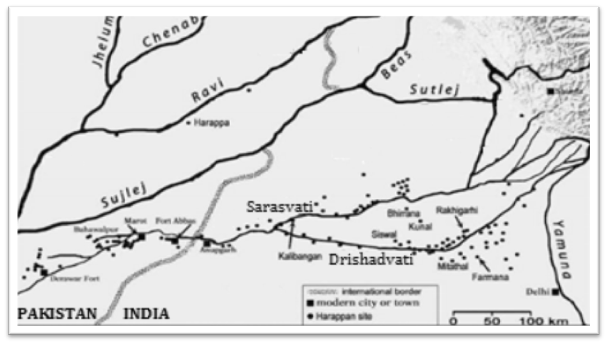

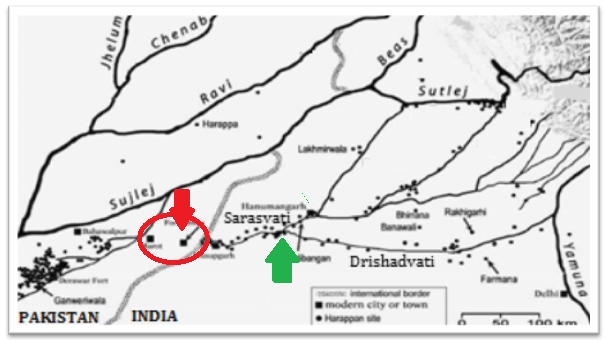

The three maps displayed here are the adapted version of Danino’s maps; in these maps, the circular black dots indicate Harappan sites and the squarish black dots indicate modern cities/towns. The dark curvy lines on the maps are rivers and the thick curvy line of lighter shade is the borderline that separates India from Pakistan.

Map No. 1 – River Sarasvati during Early Harappan Phase

Sarasvati’s seemingly uninterrupted flow during circa 3300–2600 BCE (Early Harappan phase) is attributed to its major tributaries – Sutlej in the west and Yamuna in the east via Drishadvati (identified with present-day River Chautang). The negligible number of Harappan sites along the course of Sarasvati, in the stretch below its confluence with Drishadvati (especially near the present-day India-Pakistan border), confirms a general trend towards aridity.

Map No. 2 – River Sarasvati during Mature Harappan Phase

A segment in the Hakra”s upper stretch (marked by a red circle and red arrow) is now devoid of Harappan sites; this indicates the disappearance of Sarasvati in that particular portion of her lengthy course, during circa 2600–1900 BCE (Mature Harappan phase). This occurred perhaps due to some tectonic disturbances that resulted in a diminished supply of waters from the Yamuna; however, a new branch of Sutlej now seems to supply copious water to the land beyond this stretch. Since the concerned segment lies below the confluence of Sarasvati and Drishadvati (pointed by a green arrow), this map testifies Pan̅chavimsha-Brāhmana’s statement regarding the location of Vinasana and also attests to Mahabharata’s accounts about the absence of Sarasvati’s visible flow between Vinasana and Chamsodbheda.

Map No. 3 – River Sarasvati during Late Harappan Phase

Sarasvati’s central basin has gone dry during circa 1900–1300 BCE (Late Harappan phase); this occurred perhaps because of a combination of factors. The major factor could probably be some natural/human activities that perhaps caused Sutlej to become almost a full-fledged tributary of River Indus, and the Yamuna to completely truncate its supply to Drishadvati; this indicates the supply of water to Sarasvati, now mainly from only the monsoon fed tributaries. Other plausible factors are the phenomena of erosion (resulting in river captures etc.), the ecological degradation, and the changes in land use and agricultural practices.

Correlation and the Conclusion:

River Sarasvati’s description, given in Balarama’s pilgrimage episode, cannot be directly correlated with any of these three maps; little analysis is required to comprehend the context. It is clearly understood from the pilgrimage details that Sarasvati’s visible flow was interrupted in the stretch that lies between Vinasana and Chamsodbheda. Nevertheless, it is mentioned that Balarama worshiped the Brahmins at Udapana (situated in this particular stretch), gave away gifts to them, and also took bath in the holy waters of Sarasvati there; not to mention the witnesses (herbs and ascetics) to her invisible current, at Udapana. This means that Udapana, and probably the whole of the concerned stretch, was inhabited by at least a few people during the Mahabharata days; perhaps the subterranean flow of the river was sufficient for their survival. Moreover, the drying up of a considerable portion of perennial Sarasvati’s lengthy course and the consequent desertion of that particular riverine stretch, are not single event phenomena that occurred over a short period of time; it was obviously a slow process involving simultaneous events that happened over several decades. Incidentally, this hypothesis is upheld by the following information, regarding the drying up of Ghaggar-Hakra (spotted in Wikipedia):

…… According to M. R. Mughal, the Hakkra dried-up at the latest in 1900 BCE, but other scholars conclude that it took place much earlier. Henri-Paul Francfort, utilizing images from the French satellite SPOT two decades ago, found that the large river Sarasvati is pre-Harappan altogether, and started drying up already in the middle of the 4th millennium BCE; during Harappan times only a complex irrigation-canal network was being used. The date should therefore be pushed back to c. 3800 BCE ……

One has to remember that Danino’s maps of the reconstruction of the Sarasvati basin’s hydrography are purely based on the distribution pattern of the riparian Harappan sites. When we analyse the three maps, taking this important criterion into consideration, it is easy for us to realise that Balarama undertook the pilgrimage during circa 3300–2600 BCE (the Early Harappan phase), because the other two maps (Maps 2 and 3) exhibit a complete absence of Harappan sites in the concerned riverine stretch. This deduced fact determines circa 3300–2600 BCE as the authentic date of core Mahabharata events (Balarama’s pilgrimage and the simultaneous Mahabharata war), thereby attesting to the traditional conviction.

Closing Message:

Suppose a team of dedicated researchers work towards proving the historicity of mythology, they would surely end up discovering material evidence for the narratives found in the ancient texts. Well, now it is time to reveal the true reason for the decline of Harappans; let me do it under the next topic.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.