About the Post:

On one hand, the Harappan Civilization continues to captivate the archaeologists, while on the other hand, the stories of Pandavas and Kauravas have been fascinating to the subsequent generations of our subcontinent. Discovery of an indisputable link between the two might solve a lot of hitherto persisting mysteries of the bronze-age Indian civilization; this sequel series, titled ‘Truth Behind the Decline of Harappans’, aims at the same.

Sneak Peek:

There is a perceptible connection between the legendary Kuru Dynasty and the historical Harappan Civilization. In the first and second parts of this topic, we analyzed the story of the Kurus thereby getting a glimpse of their credible link with the Harappans. Now, in this part-3, let us focus on the significant aspects of the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization……

The Harappan Dominion:

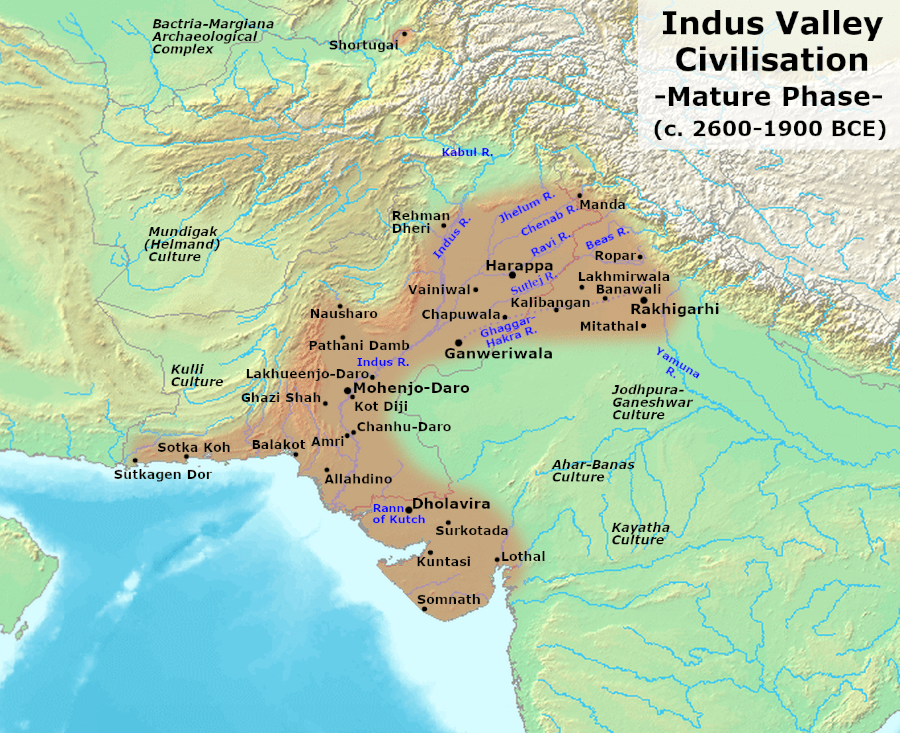

The Indus Valley Civilization thrived during circa 3300–1300 BCE in the north-western regions of South Asia. It was the most widespread civilization of its times, with its sites spanning an area stretching from northeast Afghanistan, through much of Pakistan, and into western and northwestern India. The eastern part of India has not yielded any Harappan site to date, but for a handful of them (about forty) in the Ganga-Yamuna Doab region. Discoveries at Daimabad suggest that Late Harappan Culture extended into the Deccan Plateau in India. Over 2000 sites have been reported until now, out of which Harappa (now in Pakistan) was the first one to be identified/excavated; hence the name ‘Harappan Civilization’. The term Indus Valley Civilization was assigned due to the initial notion that this culture flourished in the basins of River Indus (which flows through the length of Pakistan), but later it was realized that a host of Harappan sites were located in the Sarasvati river basin (identified with that of present-day Ghaggar-Hakra river); thus the name ‘Indus-Sarasvati Civilization’ was designated to the Harappan Culture. Despite the great numbers, there are only five major urban sites identified so far; they are Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Dholavira, Ganeriwala, and Rakhigarhi.

Chronology:

Wikipedia gives a detailed chronology including the timeline of pre-Harappan and post-Harappan periods, along with that of the concerned Harappan era (3300–1300 BCE). However, I chose to present the chronology table provided in the book titled ‘The Lost River’, authored by Michel Danino, in which the duration of each Harappan phase (Early, Mature and Late) is tabulated according to the recent views of a few archaeologists – Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, and Gregory Louis Possehl.

| Phase | Chakrabarti | Kenoyer | Possehl |

| Early Harappan | 3500 – 2700 BCE | 5500 – 2600 BCE | 3200 – 2600 BCE |

| Mature Harappan | 2700 – 2000 BCE | 2600 – 1900 BCE | 2500 – 1900 BCE |

| Late Harappan | 2000 – 1300 BCE | 1900 – 1300 BCE | 1900 – 1300 BCE |

The Early Harappan Phase is categorized under/as the Regionalization Era (circa 5500–2600 BCE), during which the scattered agro-pastoral settlements became established on the alluvial plains of the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra river valleys. As these settlements grew from small villages to large towns and market areas, they developed a higher degree of regional and internal social differentiation. This can be seen in the construction of walled settlements with segregated domestic and public structures and is also reflected in the greater varieties of material culture; the virtual explosion in material culture during this era makes it impossible to discuss all of the relevant data.

The term Indus Valley Civilization is actually synonymous with the next phase in order, which is the Mature Harappan Phase, also referred to as the Integration Era (2600–1900 BCE). This phase is characterized by the emergence of numerous urban centers and smaller regional towns. At this time we see the common use of a writing system found primarily on pottery or on inscribed seals and tablets. Standardized cubical stone weights are found at all major sites along with similar styles of pottery vessels and a wide range of other objects. Various categories of evidence indicate the presence of distinct social and economic classes, both within the cities as well as in the surrounding hinterland. Perhaps even more important is the evidence for political and ideological integration of major settlements and the emergence of what may be termed ‘city-states’.

The final phase of the Indus Tradition is referred to as the Late Harappan Phase or Localization Era (1900–1300 BCE). During this time there is evidence of major transformations in the socio-economic and political organization of cities and regional settlements. While there are some important continuities that link this period with earlier cultures, there are nevertheless significant changes in technology and production that are in turn linked to changes in stylistic and symbolic aspects of the material culture. The most significant changes are seen in the disappearance of Indus writing, standardized weights, and the breakdown of long-distance trade. By the end of the Localization Era, the socio-political and ideological aspects of the Indus Tradition have been radically transformed and reflect the emergence of a new cultural tradition that incorporates a much wider geographical area extending from the Indus to the Ganga and Yamuna alluvial plains.

Town Planning:

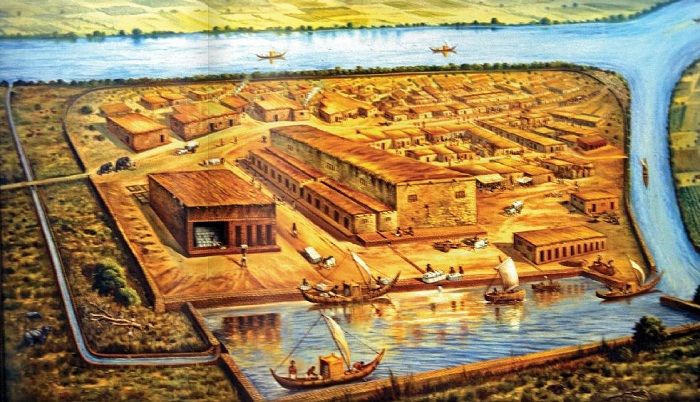

The advanced architecture of the Harappans is clearly displayed by their granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls; as a special case, the Harappan site at Lothal boasts a dockyard also. The massive walls of the cities most likely protected the Harappans from invasions, besides facilitating controlled trade. A typical Harappan city/town was divided into two parts – upper town and lower town. The upper town (usually present on the western side) is often referred to as the citadel mound, by the archaeologists; built on an artificially raised ground, it was perhaps an administrative enclosure. The lower town (always located on the eastern side) generally housed the residential buildings of common people. The bricks used by the Harappans always confined to the 1:2:4 ratio, throughout their widespread entity. Their cities were well planned with wide, grid-patterned street layouts and impressive drainage systems. Apart from the facilities like public wells and reservoirs, individual houses enjoyed the luxury of private wells, bathing platforms, and restrooms (toilets).

Trade:

Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, in his Indira Foundation Distinguished Lecture (2016), mentions the conceivable interactions between the Harappans and their contemporaries – the bronze-age civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. There is solid evidence to prove the Harappan – Mesopotamian trade relationship; however, archaeologists have not found credible clues suggesting trade contacts with the other two. Nevertheless, the internal trade activities of Harappans are quite explicit. Michel Danino confirms that there is evidence of a flourishing and varied industry during the Mature Harappan Phase. He also mentions the proof of brisk internal trade and active foreign trade with Mesopotamia, during this phase; it does seem that workshops or small industrial settlements were set up particularly for the export of goods, especially along the coast. The evidence, however, is strangely one-sided; hardly any object of Mesopotamian origin has emerged from the Harappan cities. Nevertheless certain cylinder seals and art-motifs exhibit Mesopotamian influence. Michel Danino also comments that the presence of Harappans (traders) is visible in the ancient region of Bactria and today’s Turkmenistan.

Seals:

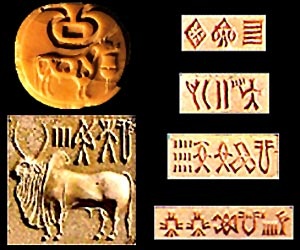

Harappans used seals and tablets of different types, with depicted images and inscriptions. It is widely believed that these items were used in trade and administration; however, there are a variety of opinions among the scholars, regarding their purpose. Some of them were round in shape while many of them were square-shaped; very few seals boasted a unique design. Rectangular tablets with images and inscriptions were also used. The seals/tablets were generally made of steatite or terracotta; however copper seals have also been discovered. Most of the seals had a knob-like feature (with pierced holes) on the rear; some of them had images and inscriptions on both sides. Archaeologists are sure that these seals were fired for several days in special kilns, making them hard enough to give repeated impressions on soft clay; such an expense of time and labour shows the importance attached to these mysterious objects.

Script:

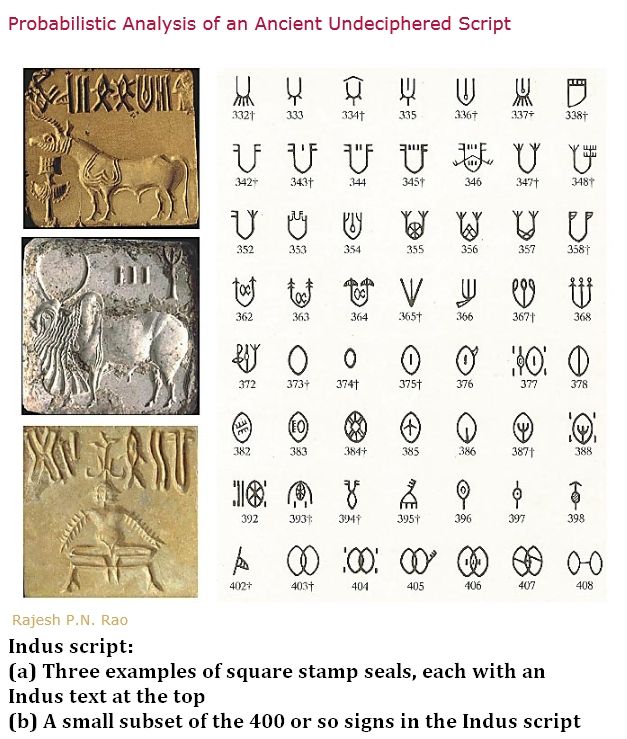

Although the pottery of the Early Harappan Phase carries a single or few Indus Symbols/Signs, a fully developed writing system appears only at the start of the Mature Harappan Phase. Seals and tablets happen to be the major sources of the yet-to-be-deciphered Harappan Script. Again, a difference of opinion exists regarding whether or not the Indus script is linguistic in nature and also about the language behind the script. However, recent research has confirmed that the entropy pattern of the Indus Script agrees with that of linguistic scripts. Despite the sincere efforts of scholars and enthusiasts, the script remains undeciphered to date.

Arts and Crafts:

Various sculptures, seals, bronze vessels, pottery, gold jewelry, and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite have been found at excavation sites. A number of gold, terracotta, and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form; other figurines include men in yogic postures, adorned females, and animals – cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. Some of the animals depicted on seals/tablets at sites of the Mature Period have not been clearly identified and hence are considered to be mythological. Harappans produced beads of different kinds and materials and were actively involved in shell-working, jewelry making, manufacturing musical instruments, building boats, metallurgical industry, etc. Some of these crafts are practiced in our subcontinent, in the same manner, even today. Certain make-up and toiletry items that were found in Harappan contexts still have similar counterparts in modern India. Harappan artifacts also include impressive toys and games.

Closing Message:

Information about the Harappan Civilization is so abundant that one can never succeed in giving a complete account of the same. My sincere thanks to the book (‘The Lost River’) authored by Michel Danino and other sources like Wikipedia, Harappa.com, Khanacademy.org, etc., for providing elaborate details about the magnificent Indus-Sarasvati Civilization. This entire part-3 is dedicated to the inevitable particulars about the Harappans and hence I could not help carrying forward this topic to the upcoming sequel.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.