About the Post:

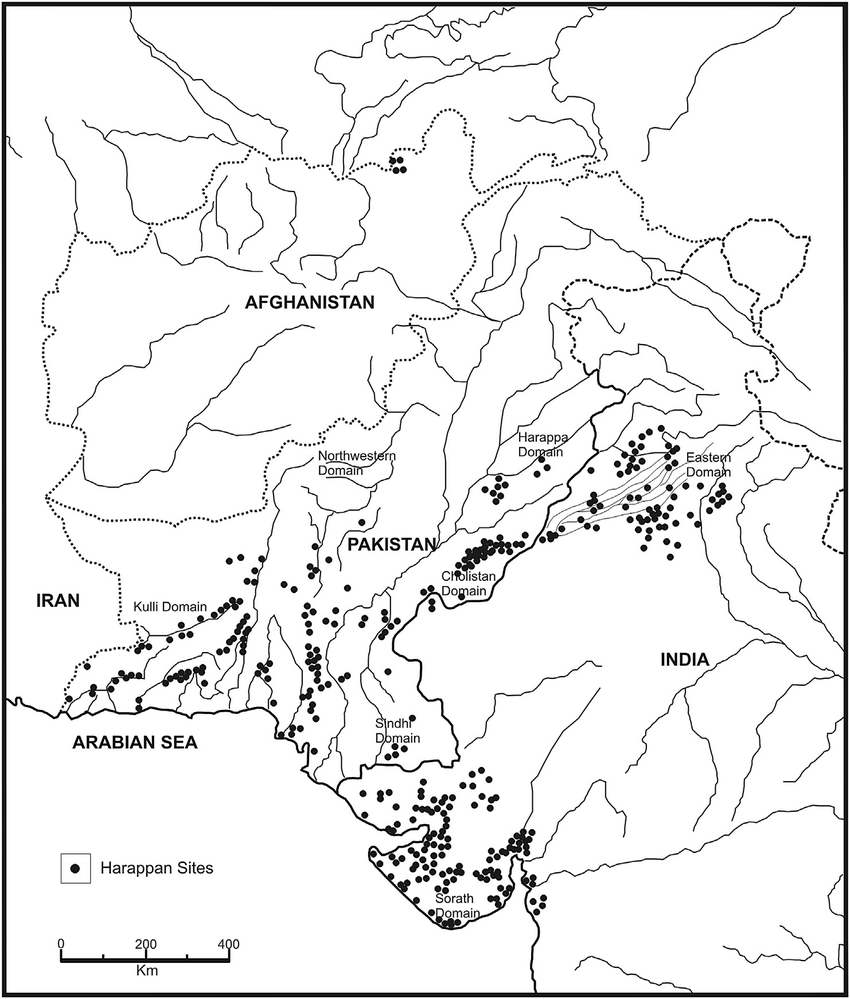

With the help of advanced tools and technologies, contemporary archaeologists are able to figure out even the minutest details about the bronze-age Harappan Civilization, such as the ingredients of their food, the components of their craft materials, the source-place of raw materials used by them, the date of their artifacts, and the like. However, certain significant aspects of the Harappans like the factor that held their vast entity together, the ‘catalyst’ that triggered their Mature Phase, the event that caused their decline, the language behind their script, the message conveyed by their inscriptions, etc. have remained mere topics of speculation, for not less than a century. Amidst such a situation, this post focuses on finding out the true reason for the decline of the Harappans.

Sneak Peek:

The aim of this topic is to re-establish the conceivable link between the historical Harappans and the legendary Kurus, in order to unveil the truth behind the decline of the Harappan Civilization. Parts 1, 2, and 3 of this sequel series gave an overview of the Kurus and the Harappans. Parts 4, 5, and 6 threw some light on the credible connection between the tangible Harappans and the intangible Kurus. This final part (part-7) shall now reveal the true cause of the decline of the glorious Harappans………

The Integration:

As a result of the analysis done hitherto, we understand that the five known major Harappan sites were actually entities that belonged to the different kingdoms (refer to parts – 4, 5 & 6), ruled by the various royal families which eventually became connected due to their mutual kinship as well as their respective relationship/friendship with the Kurus of the Mahabharata times (circa 3250–3100 BCE); needless to say, this royal net-work was knit around the strength and strategy of the Kurus. In my humble opinion, the Harappan sites of Afghanistan, Balochistan, and the western region of Pakistan can also be attributed to the Kurus, owing to their affinal ties with the Gandharas, the Madras, and the Shibis; perhaps the Kambojas/Parama Kambojas too should be mentioned in this context. Thus we realize that it was the rapport among these related royal families that held the far-stretched Harappan entity together; here I recall Kenoyer’s remarks about “the evidence for political and ideological integration of major settlements”.

In the second sequel of this topic, we inferred that the Mature Harappan Phase was supposedly the result of the relocation of Kuru Kingdom’s capital from Hastinapur to Kausambi during circa 2750–2600 BCE, yet it is too strange that a typical Harappan site is not found at Kausambi. Similarly, the present-day Bairat in Rajasthan (supposedly the Virata-nagara of Mahabharata days) seems to be devoid of Harappan sites despite the close relationship that existed between the Viratas and the Kurus. The same is the case with ‘Drupad Kila’, located 5 km away from the present-day sleepy village of Kampil in Uttar Pradesh. Kampilya of the Mahabharata days was the capital of South-Panchala Kingdom which was ruled by Drupada, the father-in-law of the Pandavas. ‘The Lost River’ (authored by Michel Danino) describes Drupad Kila as a rectangular settlement of 780*660 m; it adds that R.S.Bisht – the excavator of Dholavira – was surprised to find that the dimensions and the orientation of the Drupad Kila coincided exactly with those of Dholavira. Danino writes, “Substantial excavations have not yet been carried out, but judging from potsherds, baked bricks, and other artifacts, the site goes back several centuries BCE”. According to G.G.Filippi, the chronology of Drupad Kila separates it from the antecedent Dholavira by a gap of about 2000 years, which means that the Drupad Kila belonged to the post-Harappan period. Nonetheless, since our research clearly points to circa 3300–2600 BCE (Early Harappan Period) as the date of core Mahabharata events, I guess the Kampilya of the Mahabharata period is located somewhere else in that region. The plausible reason for the absence of Harappan sites to the east of Ganga- Yamuna Doab, despite the presence of the Kurus and their relatives there during the ancient past, is perhaps the continuous occupation of the Ganga-Yamuna-River-Valley for several thousands of years, unlike the prolongedly abandoned and hence largely intact Harappan sites of western India; thus there is a possibility that the proto-historic Harappan cities/towns of eastern India are currently either still undiscovered or totally unrecognizable.

The Decline:

Initially, the abandonment of the sophisticated Harappan habitations was attributed to the Aryan Invasion Theory; the later archaeological discoveries proved the theory wrong. Hence, the drying up of River Sarasvati and the change in climatic patterns were suggested as the reasons for the fall of the Harappans; however recent research pronounces that climate change was probably not the sole cause for the collapse of the Harappan Civilisation in the Indus-Ghaggar-Hakra-River-Valleys. The latest studies show that the Harappans did not give up despite the decline in the monsoon; they coped with it by changing their farming practices.

Michel Danino writes, “in the terminology proposed by Jim Shaffer, the Late Harappan phase (roughly 1900–1300 BCE) is called the ‘Localization Era’, to reflect the splintering of Harappan tradition into localized forms no longer cohesively held together.” Thus, according to the opinion of the archaeologists, the Harappan Civilization did not end in circa 1300 BCE; it rather began to disintegrate around that date, by undergoing a series of transitions that reflect both continuity and change. The real cause of the decline of the Harappans however remains a mystery to date. Nonetheless, I believe that the age-old Puranas and Itihasas of our subcontinent are capable of solving this puzzle.

The Harappan Civilization which was at its peak during circa 2600–1900 BCE, began to collapse around 1800 BCE; on observing Table-1, we realize that it was the reign of the Kuru-king Brihadratha/Vrihadratha that prevailed around that date (i.e. either 1883–1836 BCE or 1836–1791 BCE). Though not much information is available about this particular Brihadratha/Vrihadratha, there are quite a few literary accounts about his great-grandson Udayana. Wikipedia informs that over the years, the Kuru Dynasty was split between Kurus and Vatsas; the Kurus controlled the Haryana/Delhi/Upper Doab, while the Vatsas controlled the Lower Doab. Later, the Vatsas were further divided into two branches—one at Mathura, and the other at Kausambi; as per the information found on Wikipedia, Udayana was a popular king who ruled the Vatsas, with Kausambi as his capital. Moreover, according to Wikipedia, the first ruler of the Bharata Dynasty (Kuru Dynasty) of Vatsa about whom some definite information is available is Satanika II alias Parantapa, the father of Udayana. These fragments of information seem to indicate that the Kuru family started to break during or just before the reign of Satanika II (i.e. more or less around 1747 BCE as per Table-1).

“With Kshemaka closing the row as the monarch this dynasty will end, this source of brahmins and kshatriyas that is respected by the seers and the godly souls in Kali-yuga. In the future there will be next the kings of Magadha……………….The line of Brihadratha (not to be confused with the Brihadrataha mentioned in Table-1)…………………..will last a thousand years”, says the Bhagavata Purana. “The race which gave origin to Brahmans and Kshatriyas, and which was purified by regal sages, terminated with Kshemaka; in the Kali age……………………I will now relate to you the descendants of Vrihadratha (not to be confused with the Vrihadratha mentioned in Table-1), who will be the kings of Magadha……………..These are the Varhadrathas, who will reign for a thousand years”, says Vishnu Purana. According to ‘The True History and the Religion of India’, authored by Swami Prakashanand Saraswati, “Vishrawa, the prime minister of Chemak, killed Chemak and took over the kingdom.”; as per Table-1, Chemak/Kshemaka’s reign got terminated in circa 1437 BCE.

Owing to the identity, role, and significance of the Kurus in the Harappan context, and also due to the chronological and circumstantial coincidences, it can be inferred that the decline of the Harappans started when the powerful Kurus got divided into two groups—the Kurus and the Vatsas—around 1747 BCE, and the unrevivable disintegration of the Harappan society began when the reign of Kshemaka/Chemak—the last king of the Kuru Dynasty—ended abruptly in circa 1437 BCE. Thus, the facts discussed so far seem to strongly suggest that rather than any other known reason, it was the disunity of the Kuru family that caused the decline of the Harappans and it was the collapse of the Kuru Dynasty that led to the final dissolution of the Harappan ‘confederation’.

Closing Message:

Having figured out the story of the Harappans, let me try interpreting the Harappan inscriptions under the next topic.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.