About the Post:

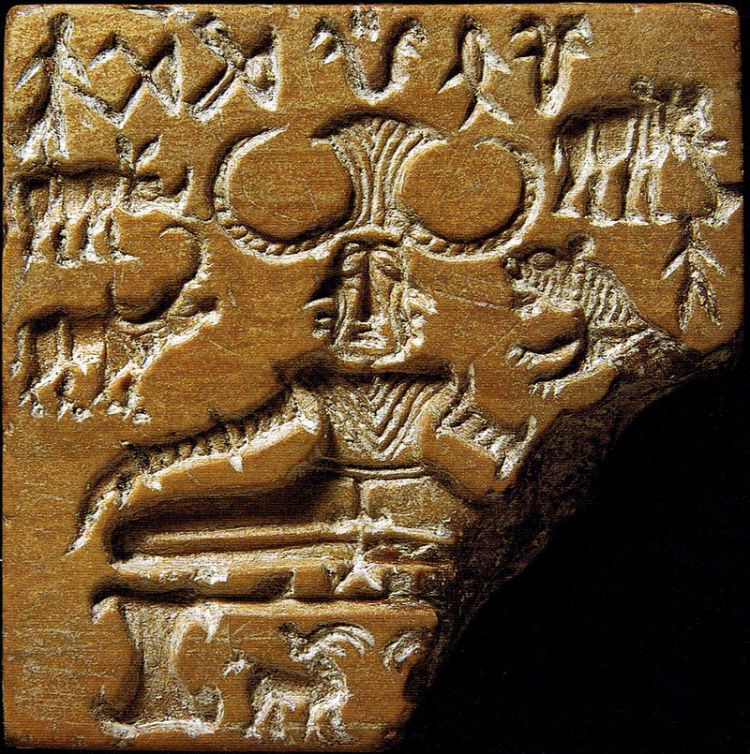

Pashupati Seal, otherwise known as ‘Indus Seal No. 420’, is one of the most popular artifacts of the Harappan Civilization; it was unearthed at Mohenjo-Daro (now in Pakistan) during the 1928-29 archaeological excavations. The seal depicts an adorned yogic figure along with a few forest animals. Sir John Marshall had identified the meditative figure as the proto-form of Lord Shiva who is also known as Pashupati – the lord of animals; thus the seal got its name. The estimated date of this steatite seal is circa 2500 – 2400 BCE; it is being preserved by the National Museum of New Delhi.

Pashupati Seal carries an inscription along with iconography. This blog has already published a post titled ‘Probing the Pashupati Seal’, which reveals the true identity of the yogic figure depicted on the seal. Now, this post shall focus on deciphering the Pashupati Seal inscription.

Sneak Peek:

This sequel series is all about interpreting the hitherto undeciphered Harappan script. Part-1 gave an overview of the Indus/Harappan script and part-2 explained the Tamil origin of the Harappan script. Dholavira signboard was deciphered in part-3. This part-4 shall decipher the Pashupati Seal inscription and also try to interpret the decoded data………

Indus Seals and Tablets:

Archaeological evidence clearly indicates that the Indus seals were primarily used for trade and administrative purposes. A large building (identified as a warehouse) at the Harappan site of Lothal (in Gujarat, India) has yielded sixty-five sealings (impressions of seals on clay) among which some still bore the impression of ropes tied around the bundles of goods. This fact implies that using the Indus seals, the Harappans produced sealings that were tied to the trade goods, just like the modern-day tags that are attached to brand-new products.

Thus, one must expect the Harappan seals and tablets to contain information that is relevant to the trade/administrative activities. The inscriptions on the Indus seals and tablets do not seem to announce the product code or price or else the quantity of the commodity; hence I guess, the Harappan seals and tablets carried the name of the source/destination of the trade goods and/or the name of the commodity/trader.

Pashupati Seal Inscription:

Previously, the website of the National Museum of New Delhi (India) use to display the picture presented here (see the image on right) on its page regarding the Pashupati Seal; now the website shows a different picture. Nonetheless, pintarest.com refers to this particular picture of the Pashupati Seal as “Pasupati Seal, National Museum – New Delhi. C. 2500 – 2400 BC. Mohenjodaro.”; so I am considering this image to be the proper (i.e. exact/un-flipped) photograph of the original Pashupati Seal.

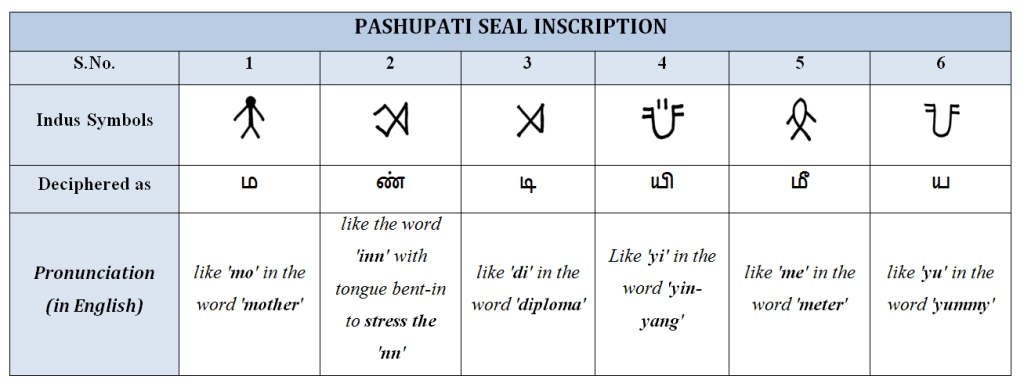

Pashupati Seal inscription is comprised of six Indus symbols. According to the opinion of a few scholars, the small human figure sandwiched between the elephant above and the tiger below is also a part of the seal’s inscription. However, it does not appear to be so because the usual practice of the Harappans is to accommodate all the symbols of an inscription together, at least by cramping them towards the end. So I am considering only the six Indus symbols that are seen at the top of the Pashupati Seal, for decipherment.

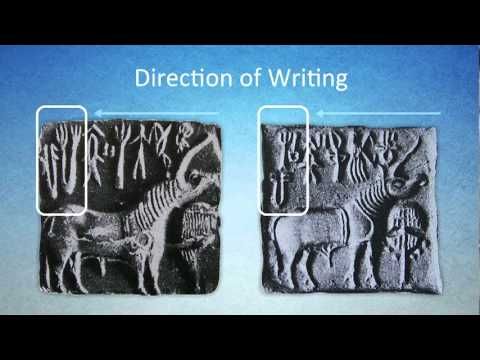

In the case of the Pashupati Seal, an empty space precedes the set of six Indus symbols, indicating that this particular inscription has to be read from right to left. However since the Indus seals were used by the Harappans for producing sealings, we have to understand that the concept of Harappan seal inscriptions is comparable to that of a modern-day rubber stamp. So, I am numbering the concerned six Indus symbols as 1 to 6, in the right to left order.

I initially deciphered and read the Pashupati Seal inscription as ‘மண்டியிமீய’. As the decipherment did not sound meaningful, I tried splitting the word into two parts – ‘மண்டி’ and ‘யிமீய’; even then ‘யிமீய’ did not seem to convey any sensible meaning. Nonetheless, after a little analysis, I inferred the word ‘யிமீய’ to be the colloquial form of ‘இமய’ (‘imaya’, with ‘i’ pronounced as in ‘it’ and ‘ma’ pronounced as ‘mo’ in ‘mother’), which literally means ‘Himalayas’. Thus, as per my decipherment, the Pashupati Seal inscription announces the name of a place called ‘மண்டி’ (‘Mandi’), in ‘இமய(ம்)’ (‘Himalayas’).

I wanted to confirm if there really is/was a city or town or village called Mandi in the Himalayas; needless to say, many cities/towns/villages of India have existed since the times of yore (e.g. Ayodhya, Dwaraka, Gokul, Hastinapur, Kanchi, Madurai, Mathura, Rameshwaram, Tiruvannamalai, Varanasi, Vrindavan, etc). So I made a Google search in order to check the correctness of my decipherment. I was simply amazed to learn that there indeed is a major town in Himachal Pradesh that has always been called ‘Mandi‘ in the local language; Wikipedia mentions that this Mandi is renowned for its age-old stone temples built for Lord Shiva. Moreover, according to my research, the iconography of the Pashupati Seal depicts Jayadratha‘s penance in the Himalayas. On realizing that my interpretation of the Pashupati Seal’s inscription and that of its iconography are complementing each other, I experienced a sense of satisfaction regarding the decipherment that I have made.

According to the website of the National Museum of New Delhi, the date of the Pashupati Seal is circa 2500–2400 BCE while as per Wikipedia, it is circa 2350–2000 BCE; “either way it is a post-Mahabharata period“, says our research. Hence, according to my humble opinion, it can be conceived that the so-called Pashupati Seal (Indus Seal No. 420) was manufactured during the post-Mahabharata period for the purpose of a Harappan trade between Mandi (in the Himalayas) and Mohenjo-Daro (in the ancient Sindh). It seems that the iconography of the Pashupati Seal was prudently devised by the concerned merchant or merchant guild to symbolize the location of the Mandi town (i.e. the Himalayas) as well as to portray the prestigious penance of Sindhu Kingdom’s former ruler Jayadratha performed in the Himalayan ambiance.

Mahabharata states that after Jayadratha was killed by Arjuna (one of the five Pandavas) in the Kurukshetra War, the kingdom of Sindhu was governed by Jayadratha’s son Suratha, whose unprecedented death caused Arjuna to crown Suratha’s son (who was only an infant/child at that time) as the king of Sindhu; the epic does not give details about the successors of Jayadratha’s grandson. However, the iconography of the Pashupati Seal seems to confirm that the kingdom of Sindhu was continuously ruled by the descendants of Jayadratha for a pretty long time, because otherwise, Pashupati Seal’s depiction of the antecedent penance of Jayadratha (during circa 3250 – 3100 BCE) would not have been possible.

Closing Message:

Hope the decipherment proposed by me for the Pashupati Seal inscription sounds sensible. We will meet again soon in part-5 for deciphering another Harappan inscription.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.