About the Post:

Most of the Harappan inscriptions are too short in length and so one might think that even if the Harappan script gets deciphered, we may not be able to learn much from the inscriptions. However my research shows that each and every Harappan seal/tablet is worth a Ph.D. topic; this post, by decoding the inscription and images found on one such Harappan tablet, shall prove the facticity of my statement.

Sneak Peek:

Part-1 of this sequel series gave an overview of the Indus/Harappan script and part-2 explained the Tamil origin of the Harappan script. Part-3 interpreted the Dholavira signboard and part-4 deciphered the Pashupati Seal inscription. Now read this part-5 to know what the Harappan tablet H2000-4483/2342-01 says……..

H2000-4483/2342-01:

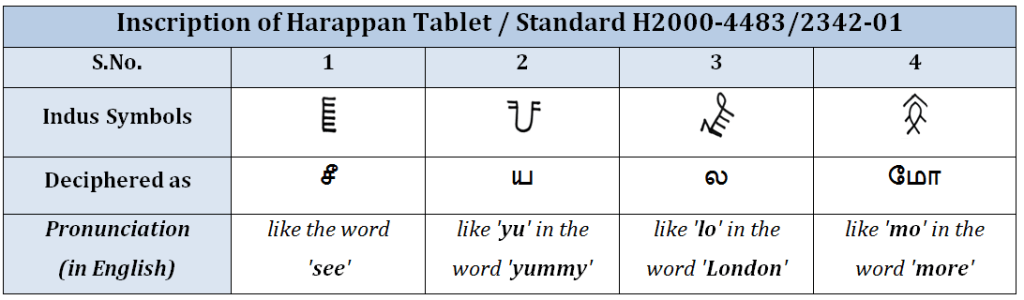

The above image shows the obverse and reverse of a Harappan tablet/standard, labeled H2000-4483/2342-01; it was discovered in 2000 AD/CE at the archaeological site of Harappa, in Pakistan. This unique mold-made faience tablet was unearthed from the eroded levels, situated west of the tablet workshop in Trench 54. On one side of the tablet is depicted a rectangular box containing 24 dots, under which is seen a short Indus/Harappan inscription. On the reverse of the tablet is found a thorny tree, under which two bulls are depicted in a fighting posture. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer (co-director, Harappa Archaeological Research Project) was kind enough to inform me that the tablet belonged to circa 2450–1900 BCE (a Mature Harappan Period).

The Decipherment:

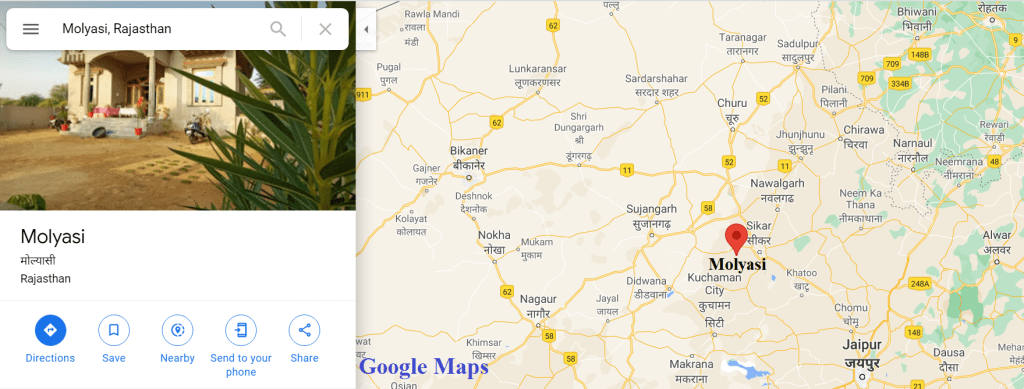

Harappan seals and tablets were evidently used for trade and administration purposes and hence are expected to contain data relevant to the activities related to trade/administration. Since place-names have always been a part and parcel of trade/administrative activities, I tried to find out if there is/was any place on earth called ‘சீயலமோ’ (‘Sīyalamō’, the ‘word’ obtained on reading the deciphered inscription from left to right) or ‘மோலயசீ’ (‘Mōlayasī’, the ‘word’ obtained on reading the deciphered inscription from right to left). Many cities/towns/villages of India have existed since the times of yore (e.g. Ayodhya, Dwaraka, Gokul, Hastinapur, Kanchi, Madurai, Mathura, Rameshwaram, Tiruvannamalai, Varanasi, Vrindavan, etc); so I thought that if there exists a place called ‘சீயலமோ’ or ‘மோலயசீ’ in current times, then there is a plausibility that it had existed during the Harappan era also. Eventually, I spotted some online information about a village called ‘Mōlyāsi’, located in Rajasthan (in India). Hence, I concluded that the inscription on H2000-4483/2342-01 was written in a right-to-left direction.

Molyasi and Harappa:

According to the online sources, Molyasi (pronounced Mōlyāsī) is a village located in the Sikar District of the Indian state of Rajasthan. However, the location of present-day Molyasi might or might not coincide with the location of Mōlayasī of Harappan times; this notion is based on the practicality that even if the name of a modern city/town/village has remained the same ever since the time of antiquity, its physical-location could have actually kept varying (at least by few kilometers) through the multifarious time-segments. Yet another factor to be considered is that there is always a chance that a major city/town of the ancient past later dwindled to become a small village/hamlet and also vice versa. Hence, we do not know whether the Mōlayasī of Harappan times was a humble village or a moderate town, or a huge city for that matter.

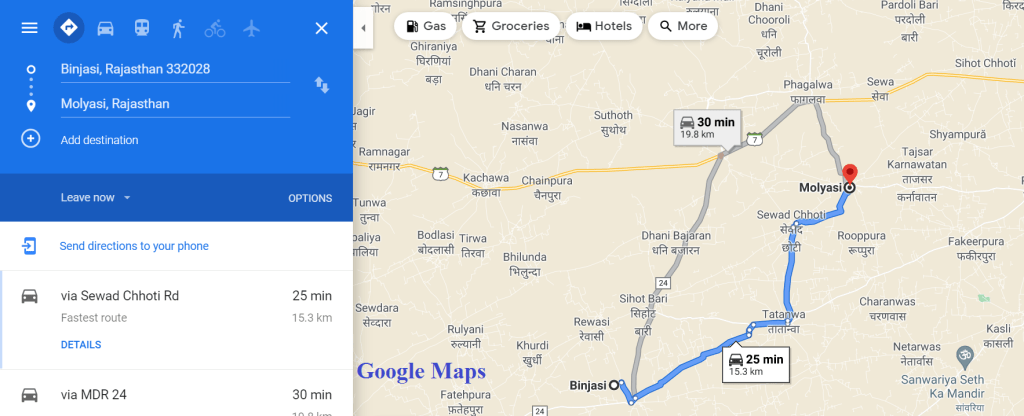

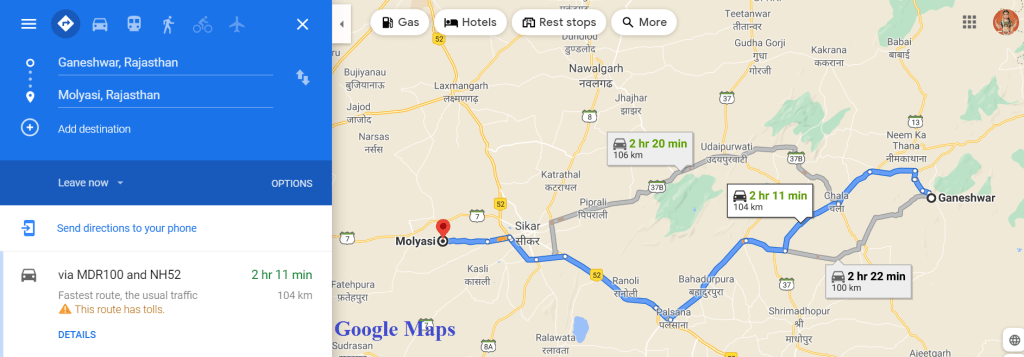

Owing to the limitations of an independent researcher, I could not verify if there are any Harappan/Harappan-era sites in the village of Molyasi. Nonetheless, an online source informs that Harappan jewellery was accidentally unearthed at Binjasi Village in the Sikar District of Rajasthan State, in August 2020; incidentally, this Binjasi is located just about 15 kilometers south-west of modern Molyasi (see Map-2). Moreover many Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) sites have been identified in the Sikar District itself; OCP (circa 3rd–2nd millennium BCE Bronze-age culture) was a contemporary neighbour to the Harappan civilization. Interestingly the archaeological site of Ganeshwar (see Map-3) in the Sikar district of Rajasthan, located about 100 km to the east of Molyasi, has yielded artifacts indicating a plausible supply of copper ore from the surrounding regions to Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro; this site belongs to the Ganeshwar-Jhodpura culture (circa 4th–3rd millennium BCE) and is situated near the copper mines of Sikar-Jhunjhunu area of the Khetri copper belt in Rajasthan. Such relevant facts seem to strongly suggest that a trade link did exist during the Harappan times, between Harappa and Mōlayasī; this, in turn, explains the discovery of the Harappan tablet/standard H2000-4483/2342-01 near a tablet workshop at Harappa.

Decoding the Motifs:

After deciphering the script, I attempted decoding the motifs (depicted images) of H2000-4483/2342-01. As mentioned earlier, a rectangular box with 24 dots is seen on one side of the tablet (just above the script); a thorny tree and two fighting bulls are present on the other side. The detailed process of decoding the motifs is explained in the following paragraphs.

The Thorny Tree:

The depicted tree (see Image-1) looks short; its branches appear drooping. The trunk of the tree looks thick and wide, with its breadth seemingly decreasing along with its height. In my humble opinion, the thorn-like parts of the tree are nothing but its narrow and oblong leaves; this inference is based on the noticeable arrangement of the thorny elements in an opposite pattern, along the length of the twigs (just like a typical opposite leaf arrangement). The very depiction of the particular tree on a Harappan tablet narrates its superior status during the Harappan times. However, unlike the Peepal/Banyan/ Neem, the depicted tree is not easily recognizable; this factor implies that its importance might have been confined to a specific zone.

Having equated the ‘மோலயசீ’ mentioned in the concerned Harappan tablet to the Molyasi village of present-day Rajasthan, I wanted to check if there is any resemblance between the state tree of Rajasthan and the tree depicted on H2000-4483/2342-01. So, I downloaded a picture of Prosopis cineraria (locally known as the ‘Khejri’) which is the state tree of Rajasthan, and compared it with the tree depicted on the concerned Harappan tablet; they did not look similar. Hence, the tree bearing the state flower of Rajasthan seemed to be the next plausible option. So I downloaded a few pictures of Tecomella undulata (locally known as ‘Rohira’), the flower of which is the state flower of Rajasthan (see Image-3); its overall appearance (refer to Image-2) seemed to resemble the tree depicted on H2000-4483/2342-01 (refer Image-1). Moreover, I found striking similarities between the morphological characteristics of Tecomella undulata (refer to Image-2) and the observable characteristic features of the tree depicted on the concerned Harappan tablet (refer to Image-1).

The morphological characteristics of Tecomella undulata as given in Vikaspedia are as follows:

1) It is a slow-growing small deciduous tree with drooping branches and stellately grey-tomentose innovations otherwise glabrous.

2) Leaves are usually opposite, 5- 10 cm long, simple, narrowly oblong, obtuse and entire with undulate margins.

The Fighting Bulls:

Having identified the depicted tree as Rohira (the tree that bears the state flower of Rajasthan), I gained little confidence about the correctness of my decipherment. However, the camel being the state animal of Rajasthan, I was quite intrigued by the depiction of fighting bulls (see Image-1) on H2000-4483/2342-01. So I tried my best to find out if there is/was a bullfight tradition in Molyasi Village or in any other part of Sikar District, but I could not obtain any such information. Nonetheless, I sought the help of Google to find out if there is any prominent connection between Rajasthan and the motif of fighting bulls.

Various YouTube videos and online news articles reported menaces caused by stray bulls that indulge in fights on several occasions, on the streets of Rajasthan. However, my aim was to check if the bullfight was a traditional sport in Rajasthan. One of my friends helped me in spotting an authentic news article referring to the bull-fight tradition of Rajasthan; immense thanks to her. The article titled ‘Adhering to SC order, no bull fight this Gopasthtami in Nathdwara‘ (Times-of-India, Geetha Sunil Pillai, Udaipur, Times News Network, updated: Oct 31, 2014, 10:41 IST) contains the following statement of Manjeet Singh, the then circle inspector at Nathdwara police station:

“There is a difference between the cow play held on Goverdhan puja and bullfight organized on Gopashtami. The strongest species of male calves and bulls are brought here and induced to fight each other while a huge crowd uproar and incite them“.

I am not aware of the name of the cattle breed seen in Image-4, but I am able to observe the similarities between the physical features of the bulls in Image-4 and that of the bulls depicted on H2000-4483/2342-01 (refer to Image-1). Kindly observe the short curved horns, stout legs, and the humpless body of the bulls depicted on the concerned Harappan tablet (see Image-1); one can notice the same features in the breed of bulls shown in Image-4 also.

Nathdwara, situated 48 kilometers northeast of Udaipur, is a town located in the Rajsamand District of Rajasthan. Nathdwara is famous for the 14th-century temple in which Lord Krishna is worshipped as Shrinathji; the town itself is popularly referred to as ‘Shrinathji’, after the presiding deity. The above-mentioned article in Times-of-India provides authentic information about the traditional sport conducted as a part of the festival celebrations at Nathdwara, in which bulls/male calves are induced to fight one another; this news article seems to testify to the decipherment proposed by me.

The 24 Dots:

The rectangle containing 24 dots, depicted on the concerned Harappan tablet, was obviously the toughest part of the riddle (see Image-5). In order to solve this puzzle, I tried to find out whether the number ’24’ is of any significance to the Rajasthanis. Eventually, I spotted reliable information regarding Rajasthan’s close historical connection with Jainism.

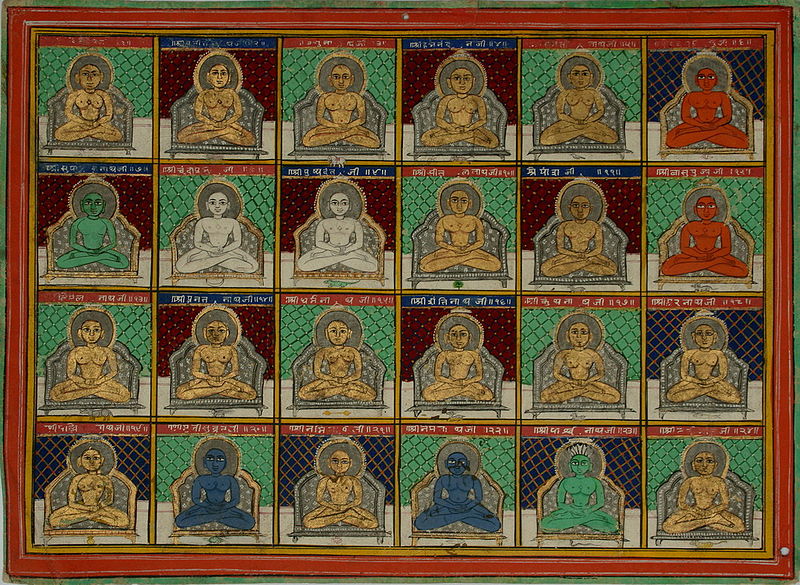

Jainism/Jain Dharma is an ancient Indian religion; followers of this transtheistic religion are known as Jains. The origin of Jainism is not clearly known. Nevertheless, Jains claim their religion to be eternal. Jain cosmology visualizes time like a wheel that has neither a beginning nor an end; the passing of time is equated to the movement of a cart’s wheel. Every rotation of the cosmic-time-wheel is divided into two halves—Utsarpiṇī (ascending half-cycle) and Avasarpiṇī (descending half-cycle). According to the Jain texts, exactly twenty-four Tirthankaras are born in each of the infinite ascending as well as descending half-cycles.

A Tirthankara (ford-maker), also called Jina (victor), is a spiritually elevated individual who has succeeded in attaining liberation from births and deaths. He is a spiritual teacher who preaches Dharma (righteous path) and is also a saviour who has made a fordable path for others to follow. Rishabhanatha and Mahavira are regarded as the first and the last Tirthankara respectively, of the current descending half-cycle. According to the general opinion of modern historians, the 24th Tirthankara Mahavira belonged to circa 6th century BCE and the 23rd Tirthankara Parshvanatha lived during circa 8th – 7th century BCE, and hence are historical characters. Moreover, contemporary scholars consider the first 22 Tirthankaras to be mythical figures.

The date of the concerned Harappan tablet is circa 2450–1900 BCE whereas according to mainstream scholars and archaeologists, the antiquity of Jainism does not go beyond the 6th century BCE. Hence it would sound far-fetched if I relate the 24 dots present on the concerned Harappan tablet to the contingent of 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism. In fact, my mentor Dr. T. Satyamurthy (former Superintending Archaeologist, ASI) stated that “Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara) friezed the ‘number’ and hence ’24’ cannot be taken to Harappan period”. So I tried to find a truly convincing explanation for the riddle of 24 dots but, despite my sincere efforts, I could not come up with a better theory than relating the 24 dots to the contingent of 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism (see Image-6), especially because Jains claim their religion to have existed since the days of yore. Moreover, I learnt that I am not the first person to find traces of Jainism in the Harappan Civilization; a few Harappan artifacts have already been suggested as a link to the ancient Jain culture. Nonetheless reputed scholars are generally skeptical about accepting this notion, as very little is known hitherto about the religion, iconography, and the script of the Harappans, and also because no solid evidence has been obtained to date to prove the claim of Jains regarding the antiquity of their religion.

Inference:

The Indus tablet/standard H2000-4483/2342-01 was discovered in the archaeological site of Harappa, near a bronze-age tablet workshop. Thus it can be inferred that H2000-4483/2342-01 was most probably manufactured at the ancient city of Harappa, perhaps for trade or administrative activity that involved the Harappan-era city/town/village called Mōlayasī, which was located in a region pertaining to the present-day Indian state of Rajasthan. Wikipedia states that the oldest reference to ‘Rajasthan’ is found in a stone inscription dated back to 625 CE/AD. However, as the Harappan tablet H2000-4483/2342-01 depicts certain Rajasthani elements, we understand that the concept of zonal attributes (i.e. regional characteristics) existed ever since at least the Harappan times.

Closing Message:

The points discussed so far seem to certify that the decipherment proposed by me for the H2000-4483/2342-01 inscription is correct. However, it is up to the scholars to decide whether or not my interpretation makes sense. Nonetheless, I would like to continue interpreting a few more Indus inscriptions in the upcoming sequels.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.