About the Post:

“We mentioned in the Introduction that the Mahabharata mentions that of the five descendants of Yayati, two became Yavanas and the Mlecchas. This seems to remember a westward emigration. This particular migration may have occurred in a very early period in the Vedic world that spanned Jambudvipa and the trans-Himalayan region of Uttara Kuru. We have later evidence for another westward movement to the lands ranging from Babylonia to Turkey”, writes Subhash Kak.

My research (TRUTH BEHIND THE DECLINE OF HARAPPANS – Part 1 to 7) proves that the Harappans were none other than the people of the Mahabharata days (circa 3250–3100 BCE) and the post-Mahabharata period (until circa 1437 BCE) who belonged to the various kingdoms ruled by the Kuru Dynasty or one of those royal clans/families that became the affinal relatives of the Kurus, during the Mahabharata period. Did the Harappans have any connection with the people of Turkey? Read this post to find out the answer.

Sneak Peek:

There are quite a number of proofs that ascertain the Harappan-Mesopotamian trade contacts, and scholars have been speaking and writing a lot about it. Here, for the first time ever, we have enthralling evidence that attests to the Harappan-Anantolian relationship……………

Indus Seal No. H-180(A & B):

A fascinating Harappan tablet was excavated by archaeologist Pandit Madho Sarup Vats in the early 1900s. I spotted this intriguing tablet for the first time as one among the images displayed by Google, when I searched for Harappan seals and tablets; initially, except for the image, I could not gather any other information about the tablet. Much later, Suzzane Marie Redalia Sullivan—the author of ‘Indus Script Dictionary’—contacted me through academia.edu for informing me that one particular side of the tablet (shown in Image-11) was numbered ‘H-180A’ while the other side of the tablet (shown in Image-12) was numbered ‘H-180B’ by the archaeologists; she added that the pictures of H-180A and H-180B can be found on page 209 of Volume-1 of the ‘Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions’ published by University of Helsinki (Finland).

Later when I requested more details from Jonathan Mark Kenoyer (co-director of Harappa Archaeological Research Project) through email, he was kind enough to inform me that the concerned Harappan tablet is a narrative terracotta tablet/sealing. Kenoyer mentioned that the tablet is made from a mold (but the mold has not been found); he also specified that the tablet was not manufactured using a seal. Regarding the date of the tablet, Kenoyer remarked that based on their (i.e. Kenoyer and his colleagues) discovery of narrative tablets in late Period 3B and 3C (of Harappan chronology), it would date between 2450 BCE and 1900 BCE.

The Inscription:

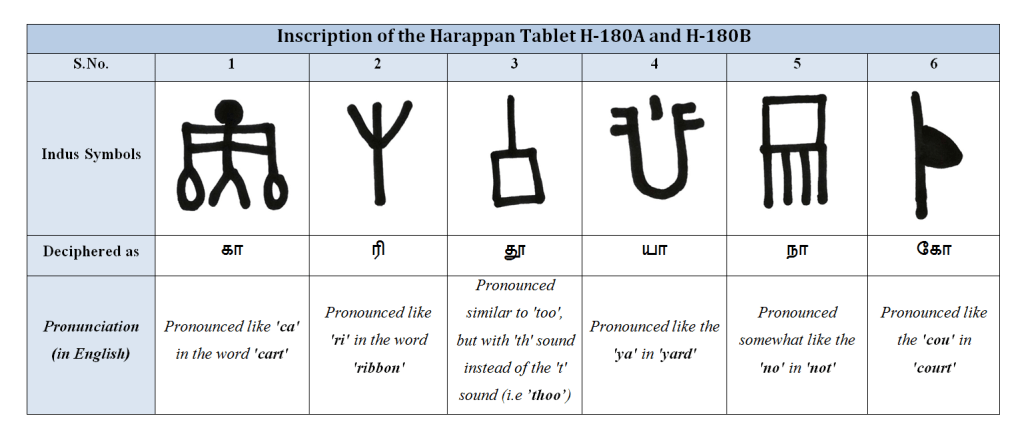

The concerned Harappan tablet contains a short inscription along with a few intriguing images (see Image-11&12). The inscription found on the obverse as well as on the reverse is identical, while the images depicted on the tablet are unique. As the director of the inscription is not indicated by the tablet, I just numbered the symbols as 1 through 6 from the left-to-right direction, for the time being.

After deciphering the inscription, I first read it from left to right (S.No.1 through S.No.6) as ‘காரிதூயாநாகோ’ (‘kārithūyānākō’); it did not sound meaningful at all. Then I read it from right to left (S.No.6 through S.No.1) as ‘கோநாயாதூரிகா’ (‘kōnāyāthūrikā’); it sounded sensible but the message was not clear. So I sought the help of Google and eventually learnt about ‘Konya’, a major city in modern Turkey (see Map-6 ); according to Wikipedia, the city’s name appears as Konia or Koniah in some historic English texts, which undeniably sounds very much like the ‘கோநாயா’ (word obtained by reading the last three symbols of the inscription in right-to-left direction). Similarly, Wikipedia’s page about Turkey states that the English name of Turkey was derived from the Medieval Latin name Turchia/Turquia (meaning “land of the Turks”); this ‘Turquia’ sounds more or less similar to ‘தூரிகா’ (word obtained by reading the first three symbols of the inscription in right-to-left direction). Thus I determined ‘right-to-left’ as the direction of the concerned inscription.

Karahöyük-Konya:

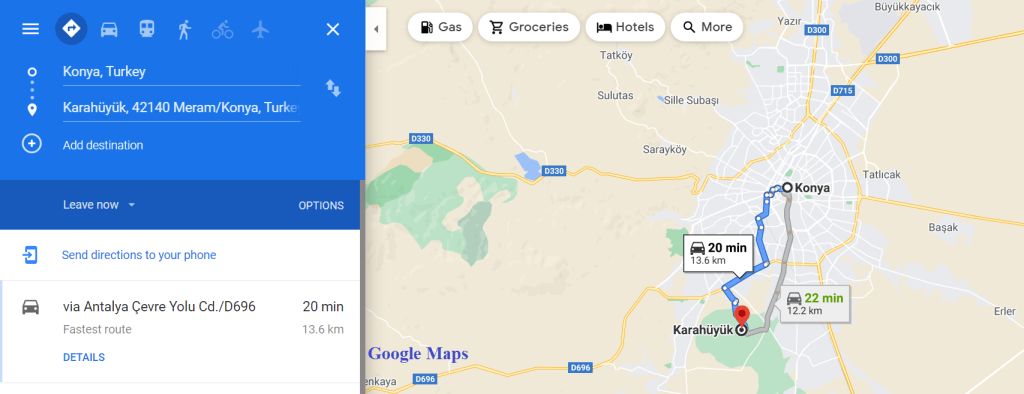

Contemporary Konya is a major city in south-central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of the Konya Province. Having interpreted the concerned Harappan inscription as Konya of Turkey, I thought of verifying the presence of Harappan-era/bronze-age sites in or around modern Konya. Eventually, I learnt that there indeed is a bronze-age site which is located just about 7 kilometers south of present-day Konya; the site is referred to as Karahöyük-Konya/Karahüyük-Konya (see Map-7).

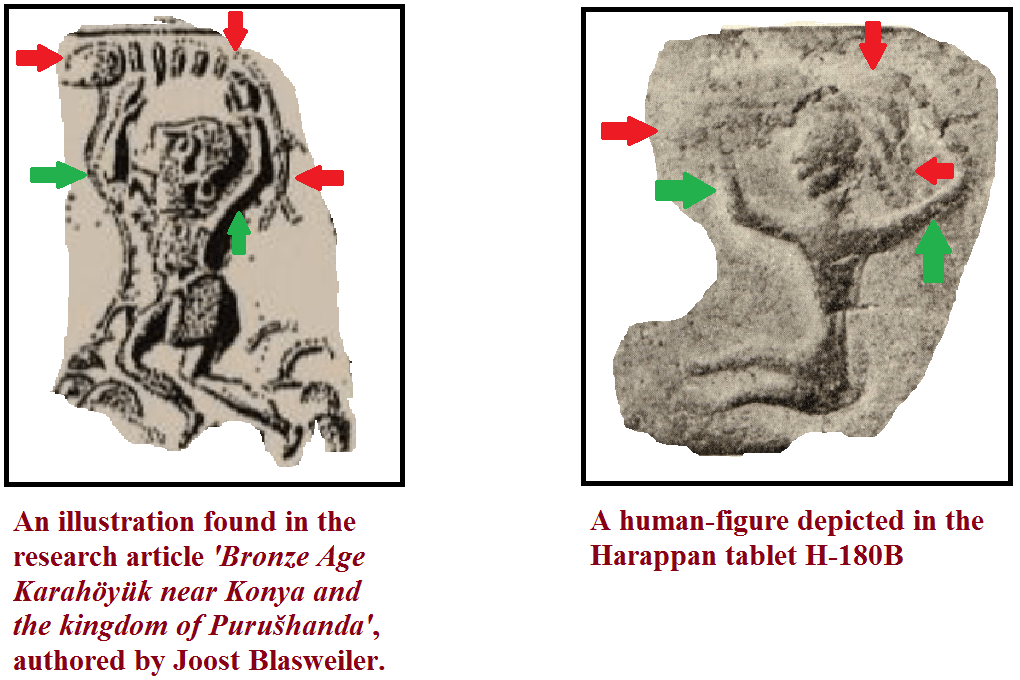

I came across a research article titled ‘Bronze Age Karahöyük near Konya and the kingdom of Purušhanda‘, authored by Joost Blasweiler. Incidentally, it happens to be the only elaborate document about Karahöyük-Konya, that can be easily accessed online. It says, “The city was, without any doubt, the capital of a principality during the end of the third millennium and during the beginning of the second millennium BCE.” The document also states, “The finding of bullae and cylinder seal imprints in Karahöyük Konya (level I and II) can indicate its position in the exchange of commodities from the west, south, and east. It is possible that its locating at the crossing of these exchange roads was the main reason for its market position.”

The Iconography:

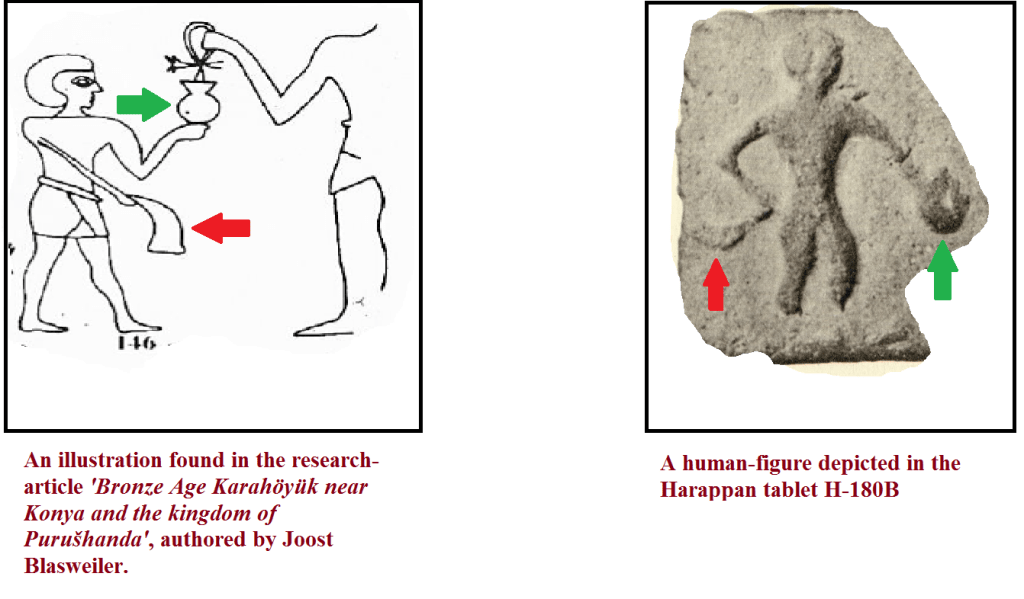

As I possess no knowledge about the culture of proto-historic Konya, and also because I could not succeed in gathering authentic details about the iconography of the concerned Harappan tablet, I am currently unable to interpret the depicted images in a proper manner. Nonetheless, certain illustrations given by Joost Blasweiler in his document about Karahöyük-Konya appear much similar to the figures depicted in H-180B.

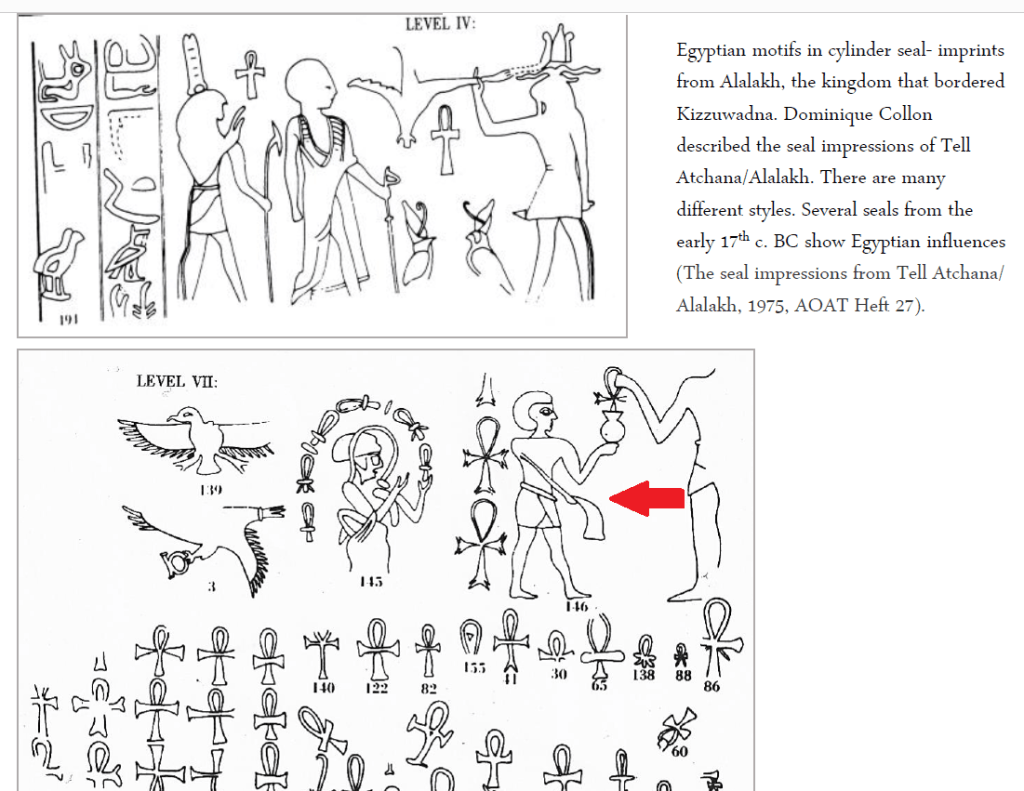

Joost Blasweiler’s illustration, seen in Image-13, shows the imprint of one of the Egyptian motifs depicted in a cylinder seal which is actually from Alalakh (a bronze-age North-Syrian kingdom); Blasweiler specifies that several seals from the early 17th century BCE show Egyptian influences (see Image-14). Blasweiler’s document states that many cylinder seals from Alalakh were found at Karahöyük-Konya. It also states, “The find of seven cylinder seals from Tell Atçana, which is the ancient city Alalakh, probably reveals Karahöyüks (trade) relation with this region.”

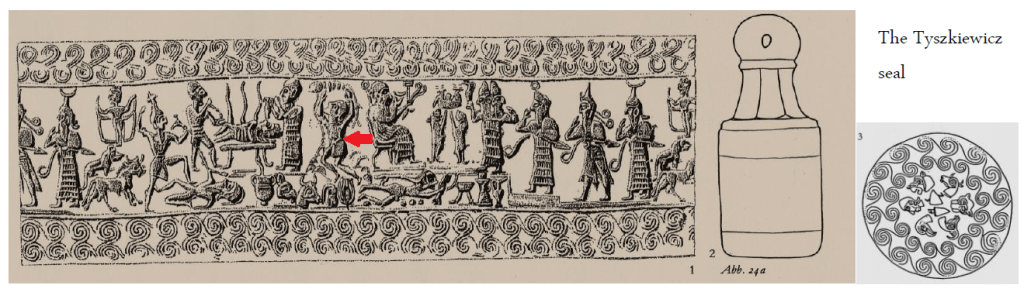

The illustration shown on the left-hand side in Image-15 is actually the imprint of one of the motifs depicted in the Tyszkiewicz seal (see Image-16) dated circa 1800 BCE by Sedat Alp; as per the caption given by Joost Blasweiler on page 19 of his document, “One assumes that this seal originates from Karahöyük near Konya.”

All that I could guess about the peculiar depiction shown in Image-17 is that it is most probably Telipinu—the Hittite god of farming/agriculture—who is portrayed in this manner in H-180A; my interpretation is based on the following Wikipedia information about Telipinu:

Telipinu was a Hittite god who most likely served as a patron of farming, though he has also been suggested to have been a storm god or an embodiment of crops……………Telipinu was honored every nine years with an extravagant festival in the autumn at Ḫanḫana and Kašḫa, wherein 1000 sheep and 50 oxen were sacrificed and the symbol of the god, an oak tree, was replanted………………………………..The Telipinu Myth is an ancient Hittite myth about Telipinu, whose disappearance causes all fertility to fail, both plant and animal……………..In order to stop the havoc and devastation, the gods seek Telipinu but fail to find him. Hannahanna, the mother goddess, sent a bee to find him; when the bee did, stinging Telipinu and smearing wax on him, the god grew angry and began to wreak destruction on the world. Finally, Kamrušepa, goddess of magic, calmed Telipinu by giving his anger to the Doorkeeper of the Underworld. In other references it is a mortal priest who prays for all of Telipinu’s anger to be sent to bronze containers in the underworld, from which nothing escapes…………………….

The Hittite empire is dated circa 1600–1200 BCE, and hence one might wonder how could H-180A belonging to circa 2450–1900 BCE depict a Hittite deity. Luckily, the ‘Abstract’ of the research article ‘The Missing God Telipinu Myth: A Chapter from the Ancient Anatolian Mythology’, authored by Esma Reyhan, clarifies this doubt:

The Hittites haven’t their own mythos. They served as a bridge to transfer this kind of literary creations from the local Anatolians (Hatti) and the other cultures (Hurri and Mesopotamia) to the ancient civilizations. The most important one of those samples is the mythos, called as “The missing God Telipinu”, which build on a theme about “turning back a god who got angry to someone or something, and went away the country, so with his departure, he took away the wealth and abundance”.

Moreover, Joost Blasweiler also refers to the culture of Hittites (esp. on page 16 of his document) in the context of the interpretation of certain archaeological finds at Karahöyük-Konya. Thus, in my humble opinion, the intriguing figure (see Image-17) in H-180A depicts Telipinu, the Hittite god of agriculture. I am aware that there are chances of my interpretation being totally incorrect in this case. However, I could not find any other suitable explanation for this peculiar portrayal.

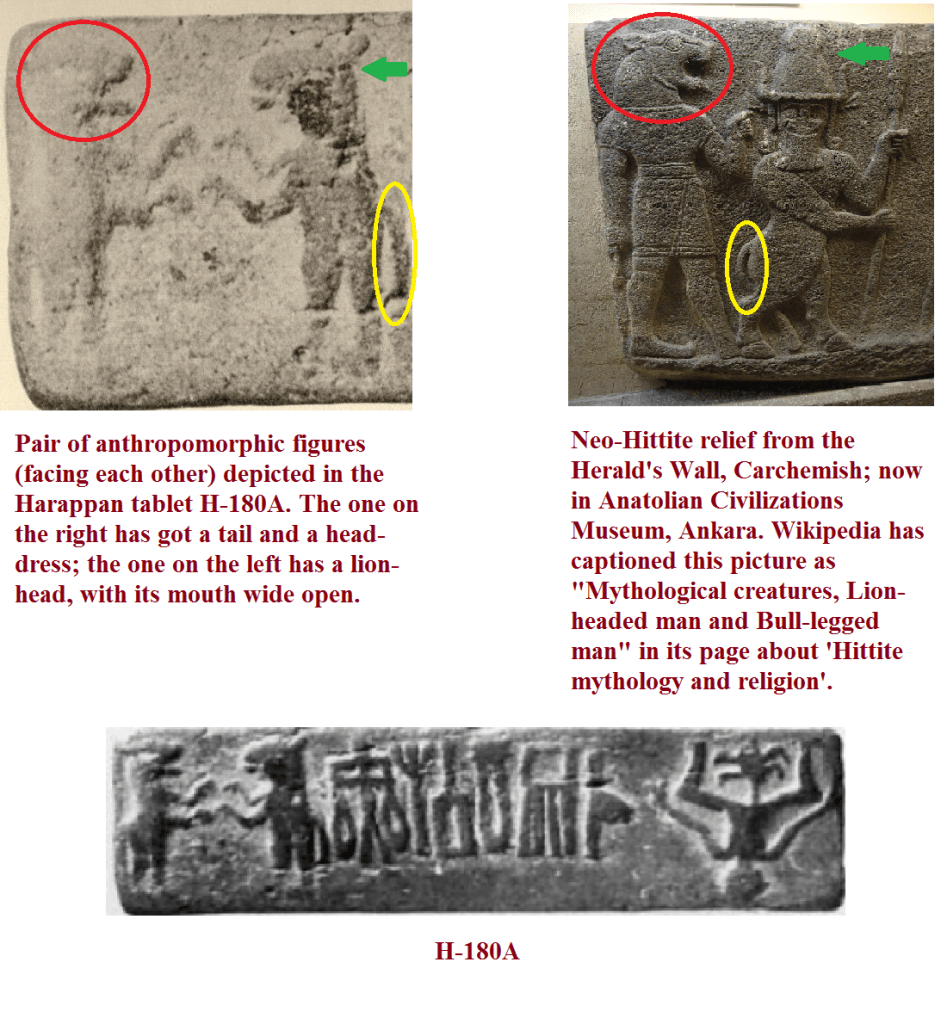

Last but not the least, we have a pair of anthropomorphic figures depicted in H-180A (see Image-18). It obviously resembles a pair of anthropomorphic personalities depicted in a Neo-Hittite relief from the Herald’s wall, Carchemish (now preserved at the Anatolian Civilizations Museum, Ankara). Incidentally, page 9 of Joost Blasweiler’s document about Karahöyük-Konya states, “………………..This may indicate that Syrian traders had visited Karahöyük several times and that the city had trade relations with kingdoms of North Syria, such as Carchemish and Alalakh.”

A Reliable Testimony:

My research apparently points to a direct relationship between the Harappans and Anatolians, during the Mature Harappan Period; however, no strong evidence has emerged to date in support of my proposition. Nonetheless, Harappa.com contains the following information provided by Dennys Frenez, which throws some light on the plausible Harappan-Anatolian trade connection during circa 2200–2000 BCE:

The westernmost object from the Indus Valley – a bleached carnelian bead – was discovered at the Early Bronze Age site of Kolonna on the small island of Aegina in Greece. Aegina is located at center of the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea, 30 km southwest of Athens and in the Bronze Age the island controlled the maritime crossroads between the Greek mainland, the Peloponnesus, the Cyclades and Crete and. Its material culture reflects all these influences and Kolonna is considered to be the earliest example of a ranked society in the Aegean outside Crete. The famous Aegina Treasure (now exhibited at The British Museum) – which includes masterpieces of gold jewellery as well as many beads and pendants made of a lapis lazuli, amethyst, carnelian and green jasper – is an outstanding demonstration of its economic dynamism. The Indus beads was part of a hoard dating to the Early Helladic III period, ca. 2200-2000 BCE, and it is quite likely that it arrived in the Aegean Sea as the result of intermediate trade though Mesopotamia and Anatolia or Syria rather than for a direct interest of the Harappan merchants in this region. However, I would love to see collections from Crete re-examined in search for Indus materials, which were very poorly known at the time of the vast excavations on the island. Other, single Indus beads are known from Troy and Hattusa in Western and Central Anatolia and from Ebla in northwestern Syria. There is no evidence instead of Indus materials in Egypt yet.

Closing Message:

All the points discussed so far in this post seem to certify that the decipherment proposed by me for the inscription of Harappan tablet H-180(A&B) is correct. However, it is up to the scholars to decide whether or not my interpretation is valid. Anyhow, I shall soon come up with the decipherment of yet another Harappan inscription in the upcoming sequel.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.