About the Post:

Lord Sōmasundara of Madurai in present-day Tamil Nadu and Lord Sōmanātha of Prabhās Patan (Dev Patan) in modern Gujarat are today recognised as two distinct Shiva Lingas situated miles apart. The former is extolled in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM as the presiding deity of Madurai, while the latter is glorified by the SKANDA PURĀNA as the principal deity of Prabhāsa-kshetra.

However, in Part 1 of INDRA AND THE INTRIGUING MADURAI OF YORE, I proposed that the names Sōmasundara and Sōmanātha may once have originally referred to one and the same Shiva Linga. In this sequel, I present the crucial clues that led me to this interpretation, offering evidence that substantiates what might initially appear to be an unfamiliar claim.

Sneak Peek:

Hints concerning the original identity of Lord Sōmasundara, along with clues to the true location of Puranic Madurai, lie embedded in the SKANDA PURĀNA and in the Sangam Literature. Read on as I trace these strands of evidence in my quest to rediscover the Madurai of yore…

Madurai and Tiru-Ālavāi:

According to the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, Lord Indra, accompanied by his preceptor Vyāzhan (i.e. Brihaspati) and other Devas, providentially beheld the Sōmasundara Linga in the Kadamba Vanam—a forest of Kadamba trees—during a penitential pilgrimage. With the assistance of his retinue, Indra cleared the dense woodland, levelled the terrain, and commissioned his celestial architect to construct a vimāna for Lord Sōmasundara, in utmost gratitude for instantly absolving him of the sin incurred upon slaying Vritra. After worshipping the deity for some time, Indra returned to his heavenly abode, as ordained by the lord.

Much later, King Kulasekara Pandyan, acting in accordance with the divine command of Lord Sōmasundara, cleared the Kadamba Vanam to establish the temple-city of Madurai. He and his successors ruled this sacred city until a cosmic deluge overtook the land, sparing only the holy sites in and around Madurai. After the earth was restored by the Supreme Divinity, King Vangiyasekara Pandyan expanded his post-diluvian capital within the bounds of the pre-diluvian Madurai as revealed by Lord Sōmasundara, and named it Tiru-Ālavāi.

Sōmasundara and Sōmanātha:

The following observations drawn from the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM, and the SKANDA PURĀNA lend support to the view that the names Sōmasundara and Sōmanātha denoted a single, significant Shiva Linga in the distant past.

The Lunar Link:

According to the SKANDA PURĀNA, the self-manifested Shiva Linga known as Sōmanātha, Sōmesha, or Sōmeshvara, is the presiding deity of Prabhāsa-kshetra. The Linga was propitiated by the moon-god Chandra of the first Manvantara through severe penance that endured for fourteen Yugas (or Chatur-Yugas). As a result, Chandra was granted two exalted boons: the Linga would bear the name Sōmanātha until the end of the Maha-Kalpa, and it would remain the family deity of the moon in every Manvantara.

Notably, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM venerates Lord Sōmasundara of Madurai as the patron deity of the Pandyas, who trace their lineage to the Lunar Dynasty.

HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM, regarded as the Sanskrit precursor of the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, extols the Shiva Linga of Hālāsya (i.e., Tiru-Ālavāi)—popularly known as Sōmasundara or Sundareshvara—as the first self-manifested Linga in Chapter 3. In Chapter 8, it identifies Meenakshi as the shakti of Sundareshvara and the presiding goddess of the Kadamba Vanam. Although the deities are frequently invoked by their Sanskrit appellations, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM also refers to them by their Tamil names—Sokkesar and Angayarkanni, respectively.

The Identical Identity:

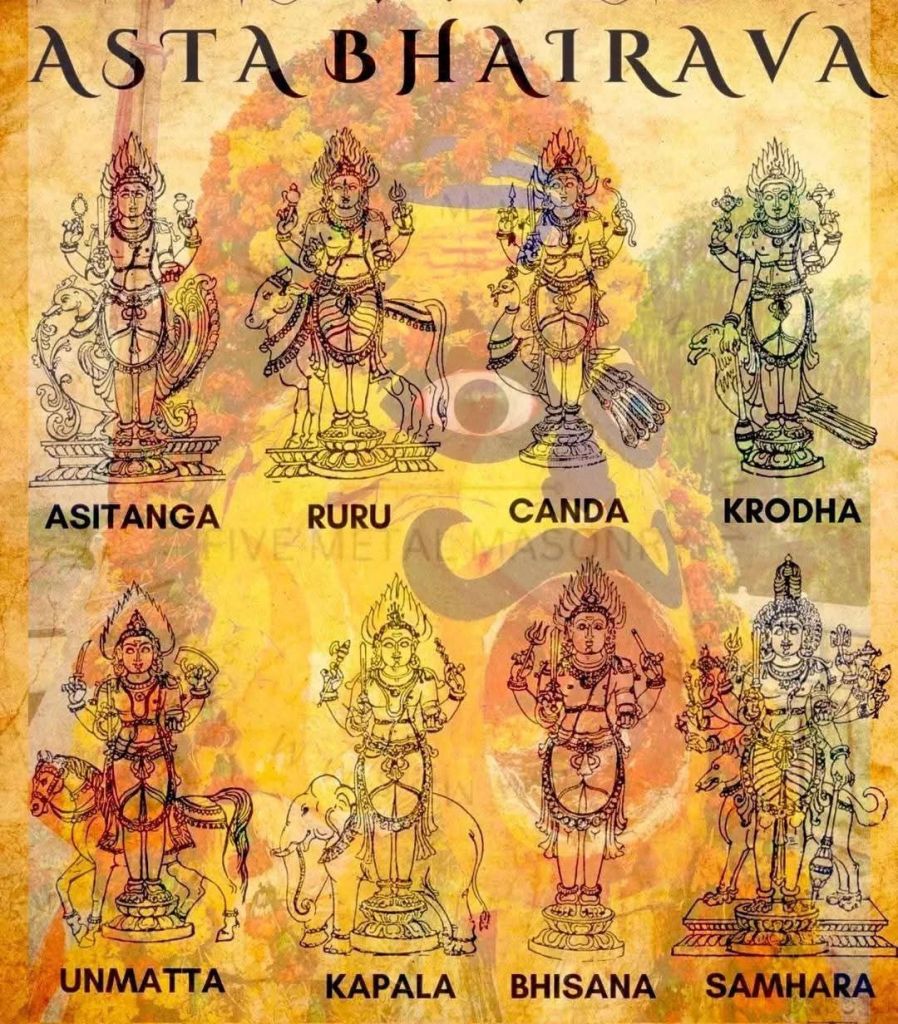

The SKANDA PURĀNA (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 7) explicitly states that the Sōmanatha Linga of Prabhāsa-kshetra, worshipped by the moon-god, was formerly known as Kāla Bhairava. Interestingly, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM (Madurai Kāndam, Tala Viseda Padalam, Verse 246), in describing the merits of observing the Attami Viratham (i.e. Ashtami Vrata) at Tiru-Ālavāi, appears to allude to an identification of Lord Sōmasundara with Kāla Bhairava. Furthermore, the text records that after presenting the vimāna to Lord Sōmasundara, Indra worshipped the lord in His eight forms around the vimāna (Madurai Kāndam, Indran Pazhi Teerta Padalam, Verse 426). This detail seems to evoke the worship of the Ashta Bhairava—the eight formidable manifestations of Kāla Bhairava (Shiva), each venerated as the guardian of one of the eight cardinal directions.

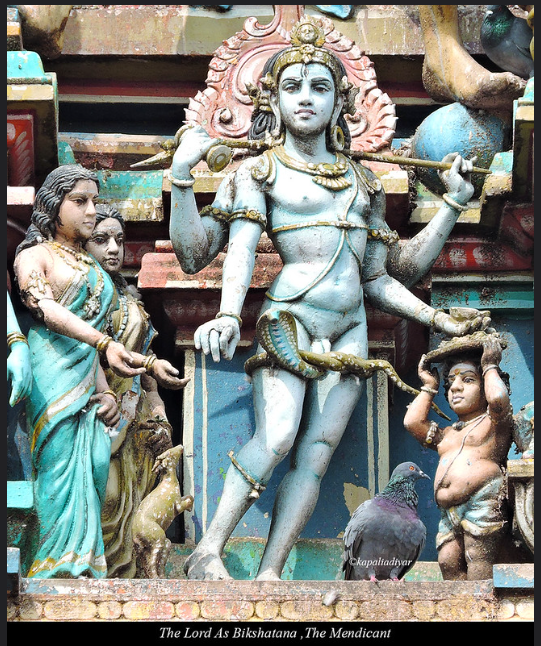

Moreover, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM recounts the episode of Bikshādanar and the rishi patnis of Dārukāvanam as one of the 64 tiruvilayādalgal. Since Bikshādanar is traditionally recognised as Bhairava, this narrative may be interpreted as an indirect indication of the deeper identity of Lord Sōmasundara. It is also noteworthy that while the SKANDA PURĀNA describes the Sōmanātha Linga of Prabhāsa-kshetra as a luminous manifestation, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM likewise repeatedly characterises the Sōmasundara Liṅga of the Kadamba Vanam as radiant or effulgent.

According to the SHIVA (MAHA) PURĀNA and the SKANDA PURĀNA, Kāla Bhairava emerged from the great flame or refulgence that manifested to proclaim the supremacy of Lord Shiva before Brahma and Vishnu. Both texts extol Kāla Bhairava as the swift remover of sins. Significantly, the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM records that Indra’s Brahmahatyā-dōsha vanished the very moment he reached the outskirts of Lord Sōmasundara’s Kadamba Vanam.

Although the SHIVA (MAHA) PURĀNA and the SKANDA PURĀNA associate Kāla Bhairava mainly with Kāsi (Vāranasi), the SKANDA PURĀNA (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 201) also speaks about the sanctity of Kālabhairava Shmashāna—the cremation ground of Kāla Bhairava—described as a distinct arid tract within the Prabhāsa-kshetra. This region is portrayed as a favourite abode of Lord Shiva, where He is said to reside perpetually, never abandoning it even at the end of the Kalpas.

In light of these significant observations, the Kālabhairava Shmashāna of the Prabhāsa-kshetra, extolled in the SKANDA PURĀNA, may plausibly be identified with the Kadamba Vanam of Lord Sōmasundara, celebrated in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM.

The True Kadamba Vanam:

As noted earlier, both the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM describe King Kulasekara Pandyan’s temple city of Madurai as having originated in a sacred grove of Kadamba trees, known as Kadamba Vanam, where the Sōmasundara Linga was enshrined. Identifying this ancient Kadamba Vanam is therefore crucial to determining the plausible location of Puranic Madurai.

Mystery of Modern Madurai:

The present-day city of Madurai in Tamil Nadu—reverentially known as Tiru-Ālavāi in religious contexts—is historically recognised as a major Pandyan centre. However, it does not appear to correspond to the Madurai or Tiru-Ālavāi described in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM. Motivated by this discrepancy, I began studying the text several years ago and have since published a series of articles proposing the Americas as the plausible landmass that once housed the Puranic Madurai.

The Actual Kadamba Tree:

Wisdomlib.org notes that the Rājanighaṇṭu, a Sanskrit lexicon, enumerates three sub-varieties of the Kadamba tree: Dhārākadamba, Dhūlikadamba, and Bhūmikadamba. Meanwhile, Wiktionary.org records five Tamil subspecies: Senkadambu, Nilakadambu, Nīrkadambu, Manjalkadambu, and Venkadambu.

In the article titled “Where once stood a forest of kadamba trees…“, A. Shrikumar notes that four different species are identified as Kadamba: Mitragyna Parvifolia, Neolamarckia Cadamba or Anthocephalus Cadamba, Haldina Cordifolia, and Barringtonia Acutangula. Thanks to the well-known temple blogger, Mr Veludharan, for bringing this informative piece from The Hindu to my attention.

Although the Burflower tree (Neolamarckia Cadamba or Anthocephalus Cadamba) is today most commonly identified as the Kadamba tree, Puranic Madurai’s conceivable connection with the Kālabhairava Shmashāna of Prabhāsa-kshetra suggests that the subspecies linked to Lord Sōmasundara’s Kadamba Vanam was more likely one adapted to arid conditions. Notably, the Sangam Literature identifies the Venkadambu (White Kadamba tree), often referred to as Marā-am or Maravam, as the variety of Kadamba that flourishes in the parched pālai landscape:

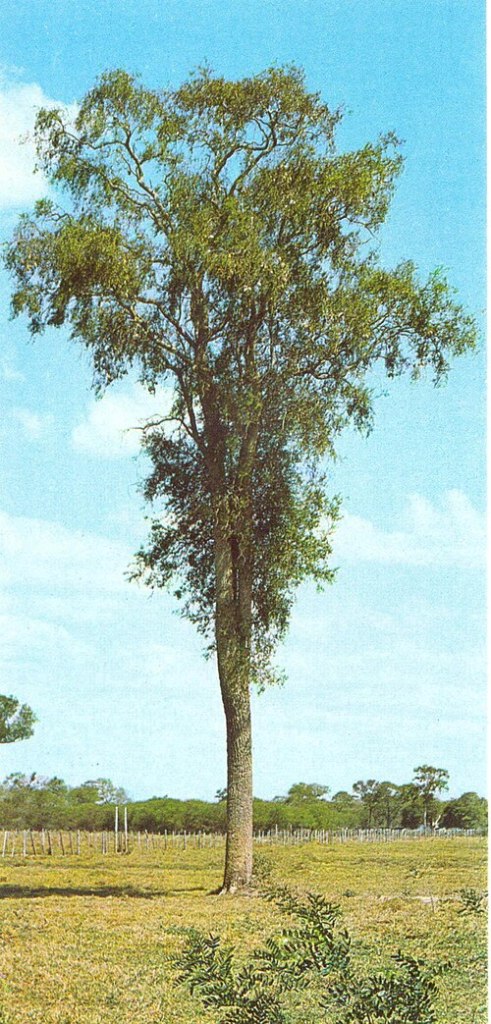

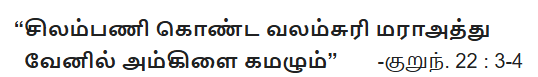

The book ‘Sanga Ilakkiyathil Thāvarangal‘, authored by Dr Ku. Sinivasan cites several Sangam verses about the Venkadambu tree. I am grateful to the venerable epigraphist S. Ramachandran for elucidating their meaning to me. Notably, among known species, Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco—native to South America—appears to closely correspond with the characteristics attributed to Venkadambu in the Sangam literature. This tall South American tree is distributed across Brazil, northern Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, and is commonly known as Quebracho blanco, Kebrako, or White Quebracho.

The name Quebracho blanco (White Quebracho) derives from the Spanish terms quiebrahacha or quebrar hacha, meaning “axe-breaker“, a reference to the tree’s exceptionally hard wood, and blanco, distinguishing it from the red variety. Interestingly, Sangam literature likewise distinguishes between Senkadambu (Red Kadamba) and Venkadambu (White Kadamba), and explicitly highlights the latter for the extraordinary strength of its timber—described as being capable of breaking even an elephant’s tusks:

Notably, Quebracho blanco produces profuse blooms, from mid-September to mid-January—the hot cum rainy season in Gran Chaco. Its inflorescences appear as clustered or whorled masses of white flowers, whose petals curve clockwise at the tips, and their pollination operates through a deceptive mechanism. Surprisingly, these features correspond to the key floral characteristics attributed to the Veṅkadambu in Sangam literature.:

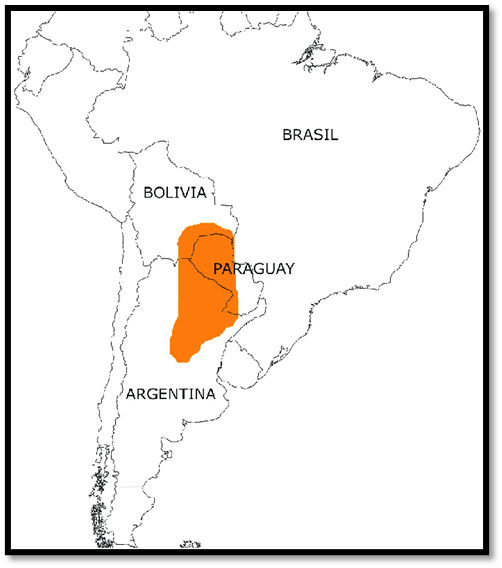

Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco is an emblematic species of the Gran Chaco, a vast semi-arid subtropical expanse of low forests and savannas in central South America covering more than one million square kilometres across eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and parts of Brazil. In light of this association, I propose that the region now known as the Gran Chaco most plausibly corresponds to the Kadamba Vanam of Lord Sōmasundara, which, in turn, appears to be identifiable with the sacred Kālabhairava Shmashāna of the Prabhāsa-kshetra.

The Territorial Truths:

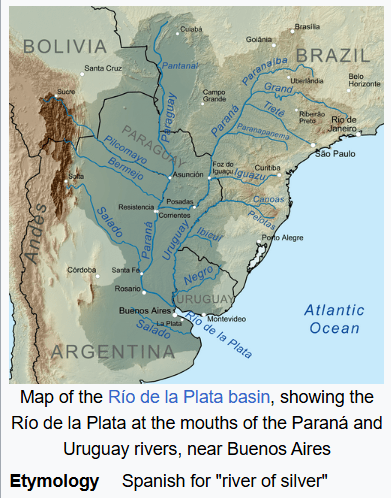

Interestingly, the Gran Chaco forms part of the Río de la Plata basin. According to Wikipedia, “plate”—an archaic term for silver—underlies the English name ‘River Plate’ of Río de la Plata, which reflects an early belief that the surrounding region abounded in silver. The same tradition also gave rise to the name Argentina, meaning “silvery land”, from the Latin argentum (silver).

Surprisingly, Madurai bears the popular epithet Velli Ambalam, meaning “Silver Hall” or “Silvery Arena.” These converging associations with silver may therefore be viewed as further suggestive links pointing toward South America as the possible location of the Puraṇic Madurai—an identification that, as discussed below, is reinforced by additional evidence.

In my article ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS OF ĀLAVĀI-MADHIL?, published in December 2024, I proposed that the zig-zag cyclopean stone walls of Sacsayhuaman in South America may represent the surviving fortifications of Tiru-Ālavāi, attributed to King Vangiyasekara Pandyan. It is gratifying to observe that this earlier proposal now gains complementary support from my interpretations regarding the Puranic Kadamba Vanam.

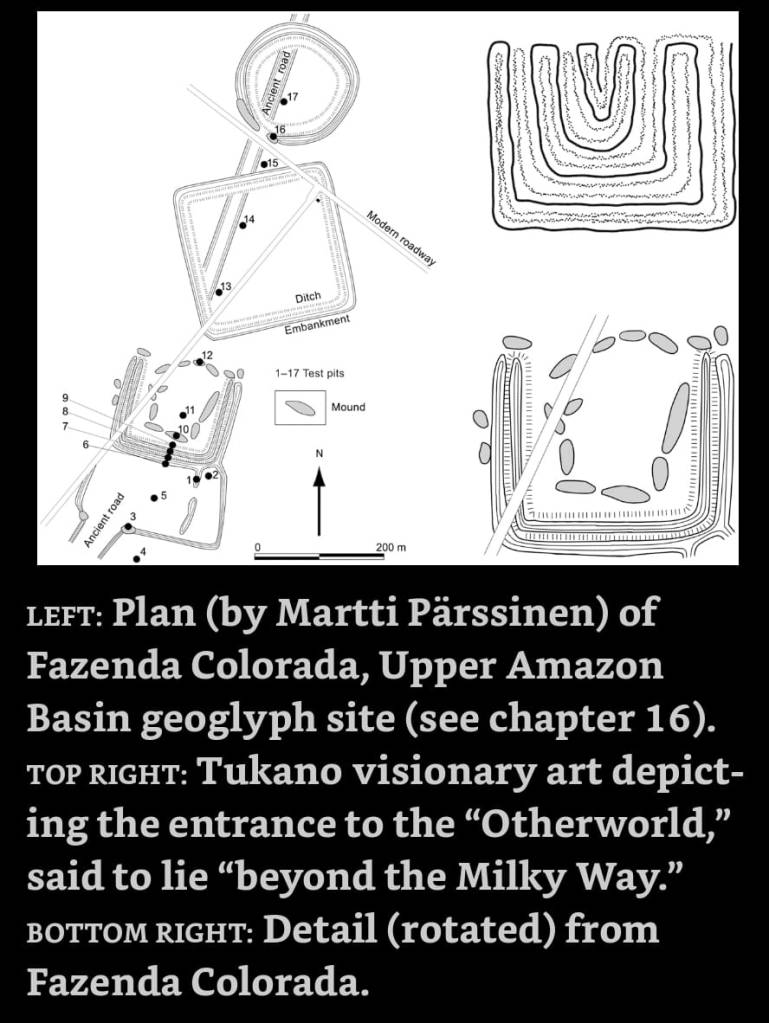

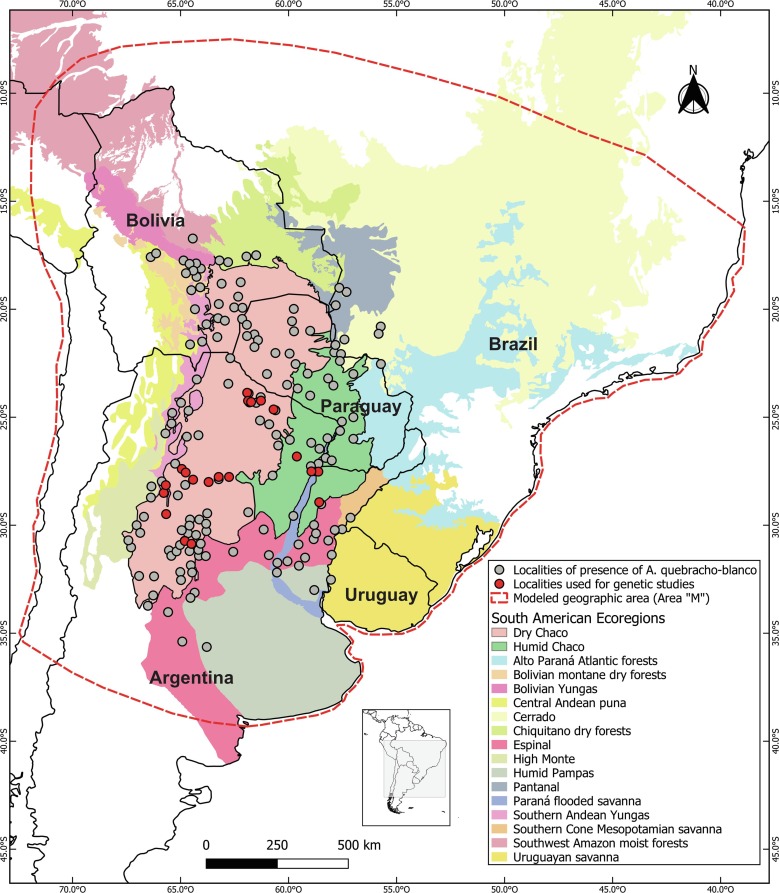

Furthermore, as potential evidence of a territorial affinity between Puranic Madurai and Prabhāsa-kshetra, the reports on numerous ancient geoglyphs discovered in the southwestern Amazon Basin—discussed by Graham Hancock in his book ‘America Before’—appear to align strikingly with the following statements about the Prabhāsa-kshetra in the SKANDA PURĀNA (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 10):

33-38. …This Prabhāsa is the centre of all piety (Dharma) and it is destructive of sins…

42. In the centre of this holy spot within the range of twelve Yojanas, O goddess of Devas’, there are thousands of Upakṣetras (subsidiary shrines).

43. Some of them are in the form of lotuses. Some are shaped like barley. Some are hexagonal; some triangular. Some are in the shape of sticks.

44. These have Brahmā etc. as the presiding deities. They are stationed in the middle of the Īśakṣetra, some in the shape of crescent and some in the shape of squares.

46. Some have the measure of a Gocarma (i.e. 150 Hastas by 150 hastas). Some have the space of a Dhanus in the middle (4 Hastas). There are crores of holy sites of the size of a sacred thread.

Taken together, the zig-zag cyclopean wall of Sacsayhuaman, the ancient geometrical geoglyphs of the southwestern Amazon Basin, and the natural distribution of Quebracho blanco collectively suggest that the Madurai of King Kulasekara Pandyan and the later Tiru-Ālavāi of King Vangiyasekara Pandyan may have encompassed a substantial portion of central South America. It is also conceivable that their territorial expanse, at certain periods, extended into adjoining regions or neighbouring landmasses.

Closing Message:

The winding path to Puranic Madurai appears to be a trail of half-veiled truths, illuminated by scattered memoirs of antiquity. When pursued with guiding intuition, it seems destined to lead us toward a long-forgotten homeland—one that binds diverse communities across the modern world through a primordial umbilical cord. May this compelling journey continue to reveal further insights, enabling us to rediscover and retrace our deepest roots.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest blog posts.

Browse the Blog page to find all the published posts.

Visit the About page for an introduction to the blog.

Explore the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of the blog.

Go through the Norms page for the blog’s terms and conditions.

Click Contact to send me a message or to find me on social media.