About the Post:

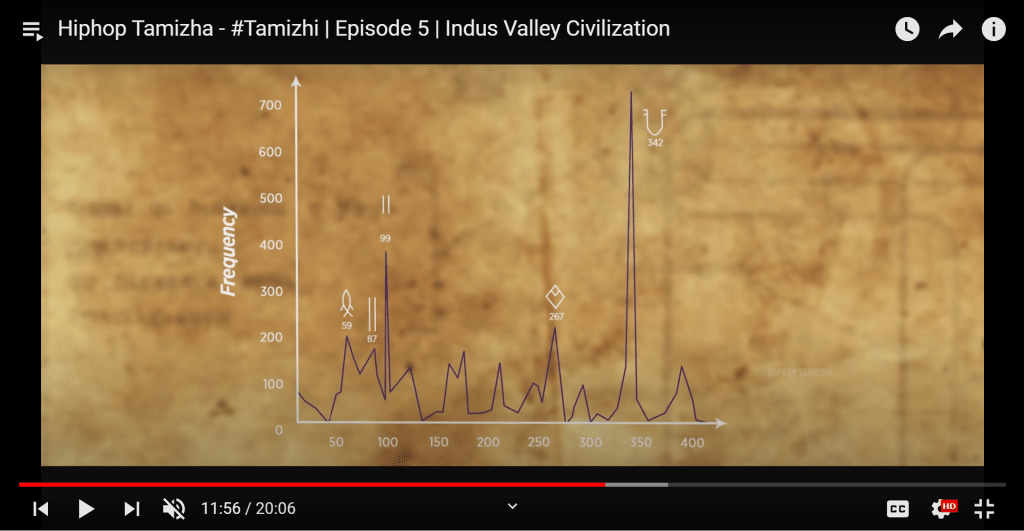

Mr. Sundar, the Director of Roja Muthiah Research Library, states that scholars had identified the Harappan script to be a Dravidian script, as early as 1924; he adds that the statistical analysis of Indus script has shown that the syntax of Harappan inscriptions agrees with the grammar of Tamil language. Iravatham Mahadevan (late), Asko Parpola, and a few other scholars have published their Tamil interpretation of Indus script/inscriptions, but none of the decipherments proposed hitherto have received scholarly consensus. However I feel that first of all, it is important to expound on the logic behind the Tamil origin of the Harappan script and hence, I decided to dedicate this post to that purpose.

Sneak Peek:

The bronze-age Harappans lived in the northern and north-western parts of the Indian subcontinent; then how come their script had a Tamil background? Read on to find out the answer………

Facts about the Indus Script:

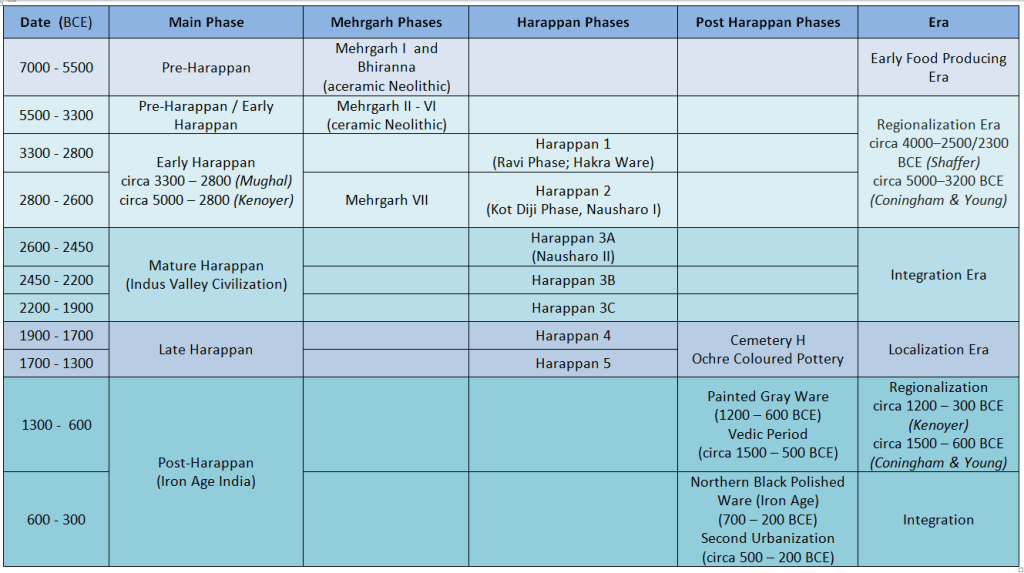

Jonathan Mark Kenoyer and his team have done significant research about the Indus script/inscriptions. In order to understand Kenoyer’s statements, we need to first learn about the Harappan Chronology; Table-1 gives the complete timeline of the Harappan Civilization, using terms designated by the archaeologists.

Let us now jot down certain important points from Kenoyer’s recent (2020) research paper:

1) The Indus script was used in the cities and towns of the Indus Civilization during the Integration Era, between 2600–1900 BCE. The evidence for the origins of the Indus script is found during the earlier Regionalization Era in the form of post-firing graffiti as well as painted on pottery. An Early Indus Script can be identified between 2800–2600 BCE.

2) The foundations of Indus writing can be traced to graphic symbols and painted designs associated with the Early Food Producing Era (Neolithic) at sites such as Mehrgarh. While many of the early graphic symbols are quite simple and may not directly link to later writing systems, some of the signs continued to be used in later periods and eventually became part of the later Indus script.

3) During the subsequent Regionalization Era (Chalcolithic/Bronze Age), there is more widespread use of graphic symbols and various types of graffiti on pottery and clay objects such as figurines and terracotta cakes. The use of multiple symbols together in varied sequences suggests that they were used to encode language or ideology. During this time period, there is evidence for the emergence of an Early Indus Script.

4) It is also possible that there are regional variations in the Early Indus Script, for example in the upper Ghaggar-Hakra River Valley sites such as Kalibangan, Kunal, and Bhirrana. Other regional forms of Early Indus writing may have been developing in Baluchistan and the Gomal and Bannu Plains of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as well as in Gujarat.

5) The development of what is thought to be a single widespread form of Indus Script is seen during the Integration Era (Bronze Age) from around 2600–1900 BCE, with the rise of major urban centers that had relatively similar economic, political and ideological systems. It is still not confirmed if this is in fact a single united writing system, though that is what most scholars assume. Based on the stratigraphic excavations of inscribed objects from the site of Harappa it is clear that the Indus Script changed over time, and that some new signs and new ways of using the script were introduced in the later part of this period.

6) Given the chronological variation seen at Harappa, it is possible that there are regional variations of the Indus Script and that some areas may have used writing in unique ways. We do have evidence that the Indus script was used to write a different language based on seals found in Bahrain and other regions of the Persian/Arabian Gulf, Iran, and Mesopotamia.

7) The Indus Script was used for around 700 years and gradually disappears during the Localization Era (1900–1300 BCE) when trade networks were disrupted and the integrated urban centers become isolated and eventually reorganized along with different cultural and economic patterns.

Language of the Harappans:

Strictly speaking, the scholars have not yet identified the language of Harappans; however, there is no dearth of hypotheses. Those who have been following my research will know by now that I always seek the help of ancient Indian texts to solve the prolongedly unsolved archaeological puzzles.

The previous research topic (TRUTH BEHIND THE DECLINE OF HARAPPANS – Part 1 to 7) of this blog revealed that the Harappans were none other than the people pertaining to the Mahabharata days (circa 3250–3100 BCE) and the post-Mahabharata period (until circa 1437 BCE), who belonged to the various kingdoms ruled by the Kuru Dynasty or one of the other royal clans/families that became the affinal relatives of the Kurus, during the Mahabharata period; the far-stretched Harappan entity obviously owed its long-lasting integrity (from circa 3300 BCE to circa 1300 BCE) to the mutual kinship/friendship that prevailed over several subsequent generations of the concerned royal clans.

Mahabharata contains a good amount of information about the Harappan Civilization. However, the epic hardly shares any detail about the language of the Harappans. Nevertheless, the Jatugriha Parva of Mahabharata says:

“……………….And after the citizens had ceased following the Pandavas, Vidura, conversant with all the dictates of morality, desirous of awakening the eldest of the Pandavas (to a sense of his dangers), addressed him in these words. The learned Vidura, conversant with the jargon (of the Mlechchhas), addressed the learned Yudhishthira who also was conversant with the same jargon, in the words of the Mlechchha tongue, so as to be unintelligible to all except Yudhishthira……………….”

Moreover, I found the following information on a website named ‘Krishna’s Mercy’:

“An old woman in Vrindavana, present at the time of Krishna’s pastimes, once stated in surprise: ‘How wonderful it is that Krishna, who owns the hearts of all the young girls of Brajabhumi, can nicely speak the language of Brajabhumi with the gopis, while in Sanskrit He speaks with the demigods, and in the language of the animals He can even speak with the cows and buffalo! Similarly, in the language of the Kashmere Province, and with the parrots and other birds, as well as in most common languages, Krishna is so expressive!” (The Nectar Of Devotion, Ch 21).

Thus we come to know that the people of the Harappan era spoke different languages; most probably there existed different dialects too. There seems to be no specific mention of Tamil as a language spoken by the people of north India during the Mahabharata days. However, my research clearly indicates that Tamil was the language behind at least half if not all of the Harappan symbols. So, how come the Harappans of the north, adopt a script of the south? Let us analyze and find out the plausible answer to this question.

Literacy of The Ancient Tamils:

According to Wikipedia, “Of the approximately 100,000 inscriptions found by the Archaeological Survey of India (2005 report) in India, about 60,000 were in Tamil Nadu.”; these are largely official inscriptions pertaining to the elites of the society. On the other hand, archaeological excavations in Tamil Nadu have yielded numerous pottery fragments with post-firing inscriptions, announcing the names of their respective owners; such inscriptions by common people of ancient times have hitherto not been found on such a large scale, in any other part of the Indian subcontinent. Most of these inscriptions exhibit the Tamil Brahmi alias Tamizhi script; the evidence obtained during recent archaeological excavations in Tamil Nadu seem to strongly suggest that the origin of Tamil-Brahmi predates the origin of the Ashoka-Brahmi (script belonging to circa 300 BCE, used by king Ashoka for inscribing his edicts in the Prakrit language), thereby indicating the plausible derivation of the latter from the former.

Epigraphist S.Ramachandran, in one of his public speeches about the Keezhadi excavations, has stated that modern scholars attribute the high literacy rate of the ancient Tamil society to the Tamil-Sangams of the bygone era. The ancient Tamil-Sangams were assemblies of eminent scholars, engaged in creating, promoting, and validating Tamil works pertaining to literature, music, and dance/drama; kings of the Pandyan Dynasty were the patrons of these Tamil-Sangams and hence the activities of the Sangams invariably took place at the capital city of the Pandyas. When all is said and done, the hitherto obtained evidence does not recommend a date earlier than circa 580 BCE for the ancient Tamil inscriptions and thus, in the opinion of the scholars, for the ancient Tamil-Sangams too. Hence, in order to explain the Tamil background of the Indus script, there is a necessity to analyze the available literary accounts regarding the ancient Tamil-Sangams.

The Tamil-Harappan Connection:

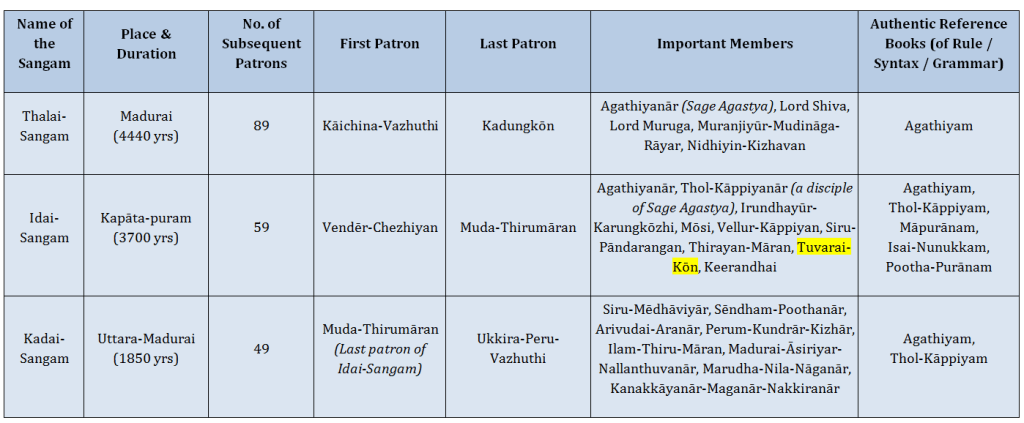

The earliest known explicit account about the Tamil-Sangams is found in the commentary by Kanakkāyanār-Maganār-Nakkiranār alias Nakkirar (a prominent member of the Tamil-Sangam), on a poetic treatise called ‘Kalaviyal-Ennum-Irayanār-Akapporul’ (‘Kalaviyal’ aka ‘Irayanār Akapporul’); the original name of the work is ‘Kalaviyal’ (meaning ‘the subject of love/courtship’) and it is said that the author of this work is Lord Shiva (Irayanār) himself. Nakkirar’s commentary on ‘Kalaviyal’ states that the kings of the Pandyan Dynasty had hosted three Tamil-Sangams namely Thalai-Sangam (the first assembly), Idai-Sangam (the middle assembly), and Kadai-Sangam (the last assembly), during the ancient past; required details about these three Sangams are given in Table-2.

In Table-2, the highlighted name Tuvarai-Kōn refers to ‘the king of Dvaraka’; it has to be noted that, along with sage Agastya and a few others, the king of Dvaraka is also listed as one of the important members of the Idai-Sangam. Moreover, there is an anecdote that speaks about the migration of Krishna’s descendants to the southern-most part of the Indian subcontinent; this story is found in the commentary on Tolkāppiyam (pāyiram; Porul. 34)—the earliest available work of Tamil literature—by Nacchinārkkiniyar, a Tamil scholar who lived during circa 6th or 7th century CE/AD. According to this legend, Sage Agastya led eighteen families of the Vēlir and the Aruvālar clans along with eighteen Vēndars (kings) from Tuvarai (Dvaraka), to the south; Wikipedia states that they eventually reached Tamraparni and got settled there. Moreover, according to the ‘Villi-Bharatam’ (Tamil version of Mahabharata, authored by Villiputthur-Azhwar), a Pandyan-princess named Chitrangada was married to Arjuna (one of the five Pandava brothers) who belonged to the Kuru Dynasty.

We already know that the cousins Krishna and Arjuna (who lived during circa 3250–3100 BCE) were in fact part and parcel of the Harappan Civilization. Hence, we understand that all the above fragments of information ultimately indicate that an intimate connection was established between the Harappans and the Tamils, during the Early Harappan period (circa 3300–2600 BCE); in my humble opinion, these facts explain (or rather justify) the Tamil background of the Harappan script.

Inferring the Information:

The first thing to be understood is that all the ongoing research and the hitherto interpreted facts about the Harappan script are purely based on the inscriptions that have managed to survive the test of time. We learn about this defunct bronze-age script only through the inscriptions found on non-perishable materials. However, there are great chances that Harappans used the Indus script to write also on perishable materials such as palm leaves, birch barks, parchment, fabrics, etc. Keeping this plausible fact in the mind, let us now analyze and interpret the facts pertaining to the Harappan script.

We have postulated that, following the establishment of an intimate connection between the Harappans and the Tamils during circa 3250–3100 BCE, the already prevailing script of the Tamil language was adopted by the Harappans for their use. In this regard, Kenoyer’s research confirms that an Early Indus Script is identified between circa 2800–2600 BCE (i.e. after circa 3250–3100 BCE).

We learnt that the Harappans spoke different languages; hence there is a chance that the Harappans not only adopted but also adapted the then Tamil script to suit their respective languages. Incidentally, Kenoyer clearly points to the plausible regional variation in the usage of the Indus script, and also to the changes that occurred over time; moreover he declares that the Harappan script was used to write different languages.

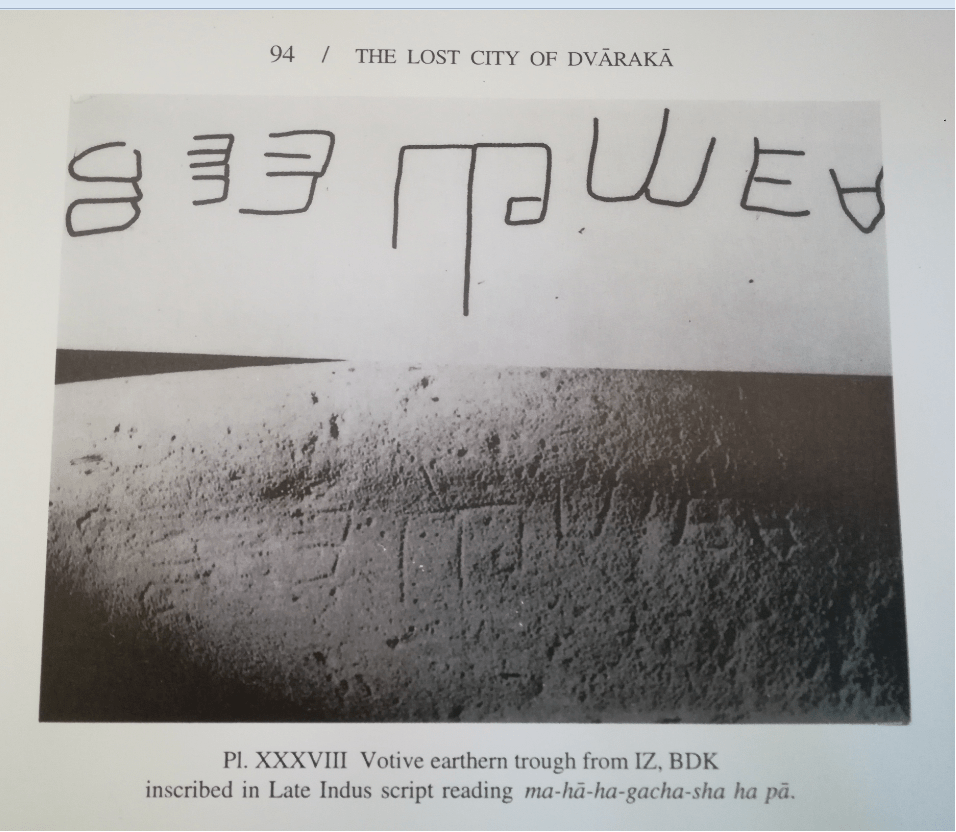

From the very fact that the Harappan symbols are found on potteries, personal ornaments, a name-board (Dholavira signboard), and a natural stone (at Dholavira), it is quite conceivable that the script was used by people from almost all walks of life. However, the major sources of Harappan inscriptions are the seals and tablets, which were evidently used for trade and administration purposes. As we know very well, the Mature Harappan Phase is characterized by extensive trade activities, whereas the Late Harappan Phase experienced a breakdown of long-distance trade; these factors obviously got reflected in the use of seals/tablets, thereby creating an illusion of the disappearance of the script during 1900 – 1300 BCE. However one can almost be sure that the Harappan script underwent a transformation during the Late Harappan Phase; this assumption is based on the discovery of the Bet-Dwaraka inscription dated circa 1500 BCE (by Dr.S.R.Rao), which is comprised of what can be termed as an evolved form of Harappan script.

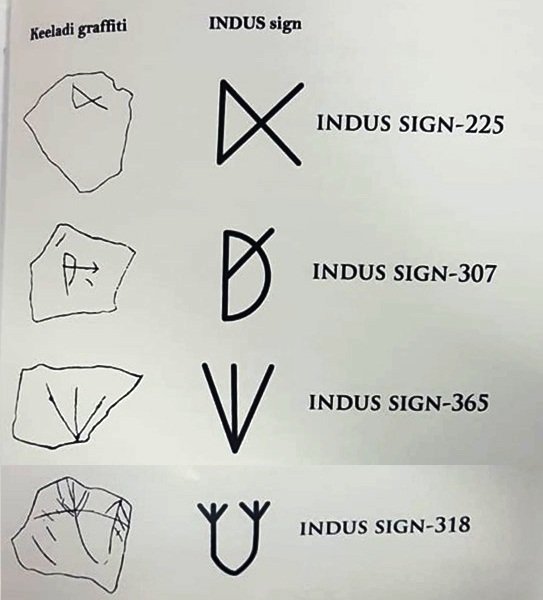

All these inferences made hitherto are purely based on the notion that the Harappans adopted the Indus script from the Tamil country. Though this hypothesis seems to be pretty much convincing, no material evidence has been obtained so far in support of this theory; neither Harappan inscriptions nor Harappan era sites have been discovered in Tamil Nadu. Of course, occasionally some of the ancient Tamil inscriptions include peculiar symbols (sort of irrelevant symbols) that resemble Harappan signs, and also Keezhadi has yielded certain graffitis which can be compared to the Indus signs; however they neither belong to the Harappan era nor can they be quoted as credible evidence. Suppose it gets proven in the future that the Indus script was not adopted from the Tamil country but was devised by the Harappans themselves, then it could only mean that Tamil was one of the prominent languages of the Harappan society, for there is no doubt regarding the Tamil origin of the Harappan script.

Closing Comments:

This part-2 narrates the plausible story behind the Tamil background of the Harappan script. The upcoming sequels shall focus on the decipherment of selected Harappan inscriptions.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for the introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Go to the Contact page to message me and/or to find me on social media.

Great article and great insights. My feedback, if it may helpful, are below:

1. Please read Asko Parpola’s view on Mahabharata story. His suggested timelines does not align with yours. His view is that they are between two steppe ancenstory arrived via two different timelines.

2. My hypothesis is that after Harrapan’s civilization was destroyed by the floods from Himalayas around 1900BC, it was pretty munch in decline for the next 900-1000 years. By this time, the language of Meluhans (meluchas) perhaps lost it written form and only been known as spoken language. It was revitalised by the refugees from Elam and Ur (Mesopotamia), escaping Assiriyan attacks and incursion from indo-european speaking Iranians by around 1000BC. Thease refugees, Haltamils (Elam) provided the structure and charactor to the spoken Meluhans language that we now know as Tamil. Hence we see references to proto-dravidian links to Elam by David McAlpin and John Marshal’s Pandyan dynasty’s link with Elam via Ay Velir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad that you read my post and also responded. Yes, I understand that the date I suggest for the Mahabharata does not agree with the notion of main-stream scholars. However, in my blog, I have been providing archaeological proofs in support of my theory; I request you to kindly read all of my research posts and let me know if you are convinced with my idea. Thank you.

LikeLike