About the Post:

The ancient Tamil epic TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, authored by Paranjōthi Munivar, recounts sixty-four tiru-vilayādalgal—divine acts/plays/pastimes—of Lord Sōmasundara and his consort, Goddess Meenakshi, the presiding deities of Madurai. The first of these sixty-four narratives describes how Indra, by the grace of Lord Sōmasundara, was absolved of the sin that he incurred upon slaying Vritra. By comparing this episode of the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM with its counterpart in the SKANDA PURĀNA, this article provides insightful perspectives on the traditional term “Ādaga-Madurai“, an ancient appellation of Madurai, also known as Tiru-Ālavāi.

Sneak Peek:

While the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM is traditionally revered as the sthalapurānam—the sacred chronicle—of Madurai, the SKANDA PURĀNA offers gleaming yet illuminating glimpses into the long-forgotten realities of ancient Madurai. Read on to rediscover the astonishing truths about the long-lost Purānic Madurai…

Madurai and Its Presiding Deities:

In Tamil, the God of Madurai is known as Chokkan, Chokkanāthan, or Chokka Lingam, while his consort—the goddess of Madurai— is called Angayarkanni or Angayarkannammai. In Sanskrit, the deities are referred to as Sōmasundara, or Sundareshvara, and Meenakshi, respectively.

Devotional literature recognises Madurai and Tiru-Ālavāi as the names of the sacred heartland of the dynastic Pandyas. However, the present-day Madurai of Tamil Nadu, although recognised as a prominent Pandyan centre in Indian history, does not correspond to the Madurai or Tiru-Ālavāi described in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM. Motivated by this intriguing discrepancy, I began researching the epic a few years ago and have since published three articles exploring the truth about Purāṇic Madurai. The one you are reading now is the fourth in that pursuit, presenting new and compelling evidence that sheds light on the fascinating realities of ancient Madurai.

The Sanskrit Source:

Paranjōthi Munivar, the author of the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, states that his work is an attempt to retell, in Tamil, the glory of Ālavāi as described in a section called Īsa/Sankara Sangitai (i.e. the Shankara Samhitā) in the (S)KĀNDAM (i.e. the SKĀNDA MAHAPURANA), one of the 18 Purānas composed in Sanskrit by Sage Vyasa. The Sanskrit source he refers to is apparently the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM. However, there are notable discrepancies between the Tamil version and its purported Sanskrit original.

According to Wikipedia, the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM is said to be a part of the SKANDA PURĀNA. If this perception is accurate, it would suggest that the SKĀNDA MAHAPURANA and the SKANDA PURĀNA are essentially one and the same work. However, this identification requires further verification.

Indra and Vritrā:

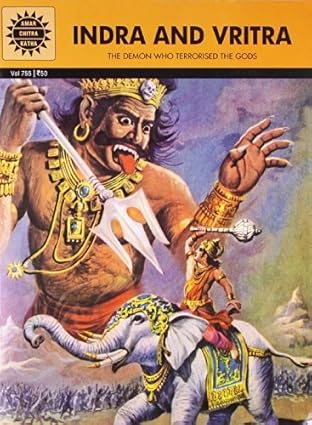

In Hindu scriptures, ‘Indra‘ is not a personal name but a title borne by the king of the Devas, the celestial beings who inhabit the heavenly realms. Each Manvantara—a cosmic time cycle—has its own Indra; the Indra of the current Manvantara is Purandara. Also known by the epithet Shakra, Indra is associated with the sky, lightning, thunder, storms, rain, rivers, weather, agriculture, and war. While the Vedic and Sangam literatures revere Indra as a significant deity, the Puranās tend to depict him as a powerful yet subordinate demigod.

According to the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, Indra slew Vichchuva-Uruvan (Vishvarupa)—the three-headed son of Thuvatta (Tvashta)—who, though appointed as the interim preceptor of the Devas, secretly sympathised with the Asuras. In retaliation, Tvashṭā performed a fire ritual to create Vritra, an Asura destined to avenge his son’s death by destroying Indra. In contrast, the SKANDA PURĀNA (Nāgara Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 8) describes Vritra as the son of Tvashta and his wife Ramā, daughter of Hiranyakashipu, born as the outcome of Ramā’s intense penance to obtain a heroic son who would embody the dual nature of a Brāhmana and a Dānava.

Indra’s Sin:

Despite the differing accounts of Vritra’s origin, both the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and the SKANDA PURĀNA concur that Indra, aided by higher deities and great sages, ultimately slew Vritra. Furthermore, both texts affirm that Indra incurred Brahmahatyā-dōsha—the sin of killing a Brāhmana—upon slaying Vritra, and therefore had to undertake a pilgrimage to atone for the transgression and relieve himself from the consequent sufferings.

Who Saved Indra?

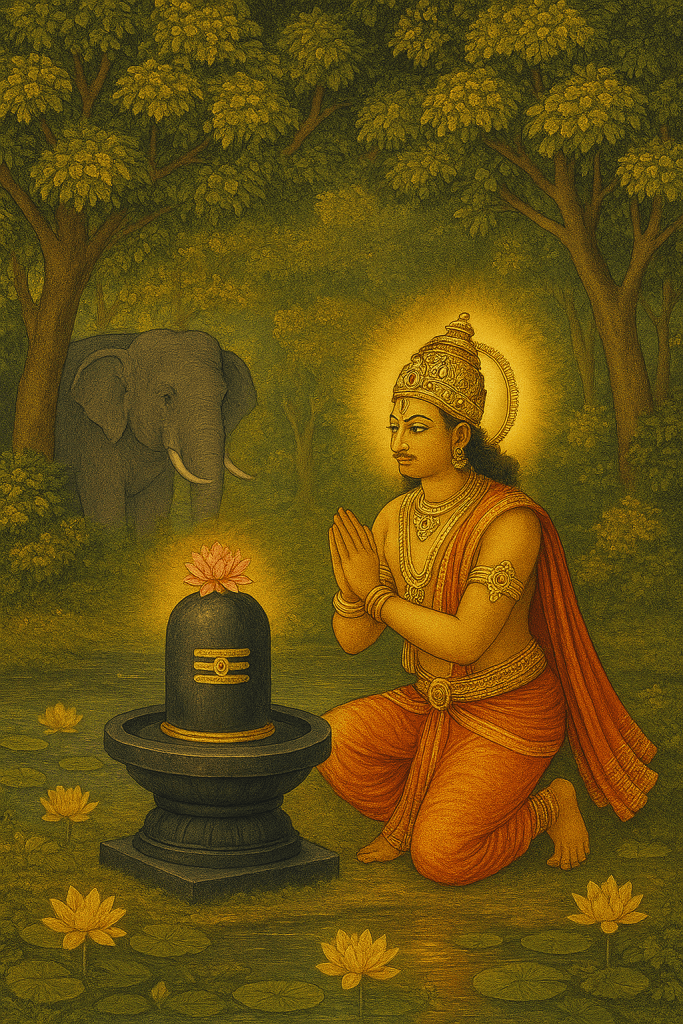

According to the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM (Madurai Kāndam, Indiran Pazhi Theertha Padalam), Indra was absolved of his sin by the grace of the Sōmasundara Linga located in Kadamba Vanam, the dense forest of Kadamba trees, later celebrated as Madurai. In contrast, the SKANDA PURĀNA (Nāgara Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 8) recounts that Indra was purified by the grace of the Hātakeshvara Linga situated in Pātāla, the netherworld.

The Confusing Claims:

The HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM describe the Sōmasundara Linga of Kadamba Vanam as the first-ever self-manifested linga (i.e. the svayambhulinga-cum-mūlalinga). In contrast, the SKANDA PURĀNA (Nāgara Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 1) states that the Hātakeshvara Linga, enshrined in the Pātāla (netherworld) region, was fashioned by Lord Brahmā from gold and was the first linga to be created and installed.

These scriptural accounts clearly indicate that the Sōmasundara Linga and the Hātakeshvara Linga are distinct from each other. Nevertheless, both are inextricably linked to the legend of Indra and Vritra. Intriguingly, the clues to this enigmatic connection remain subtly embedded within the scriptures, awaiting deeper exploration.

The Conspicious Clues:

The SKANDA PURĀNA (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 347) records that the Hātakeshvara Linga, having emerged from the subterranean realms, was installed by Sage Agastya at Prabhāsa-kshetra. However, according to the same text (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1), a svayambhulinga known as Sōmesha, Sōmeshvara, or Sōmanātha is regarded as the presiding and principal deity of Prabhāsa-kshetra, although the scripture also acknowledges the presence of other lingas within the sacred complex.

The Sanskrit word Prabhāsa denotes splendour, beauty, lustre, brilliance, and radiance. Consequently, the name Prabhāsa-kshetra is generally rendered as “the holy land of radiance” or “the sacred region of effulgence”. The corresponding Tamil term for Prabhāsa is Oli, meaning light. Interestingly, the PATTINAPPĀLAI (lines 274–275), a work of Sangam literature, refers to a people called Oliyar, interpreted by scholars as the inhabitants of a region known as Oli Nādu (Oli means “light“ or “bright” and Nādu means “land” or “country”). If my interpretation is correct, Oli Nādu may represent the Tamil equivalent or translation of Prabhāsa-kshetra.

The Merged Memories:

The MAHĀBHĀRATA (Tīrtha-yātra Parva, Section CXXX) mentions Prabhāsa as the favoured spot of Indra, a place believed to absolve all sins. This suggests that in due course, the legend of Indra and Hātakeshvara became merged with the sacred history of Prabhāsa-kshetra.

While the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM venerates Lord Sōmasundara of Madurai as the patron deity of the Pandyas, who trace their descent from the Lunar Lineage, the SKANDA PURĀNA (Prabhāsa Khanda, Section 1, Chapter 7) recounts that Chandra, the moon-god, received a boon whereby Lord Sōmanatha, the presiding deity of Prabhāsa-kshetra, would remain the family deity of the moon in every Manvantara. This narrative reveals an undeniable connection between Madurai and Prabhāsa-kshetra, illuminating the mystical bond linking the Sōmasundara Linga and Hātakeshvara Linga.

Vaigai and Vegavatī:

The TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM extol Ālavāi (i.e. Madurai) as the foremost among the sixty-eight Shiva Kshetras. However, the SKANDA PURĀNA (Māheshvara Khanda, Section 3b, Chapter 2) does not mention Hālāsya—the Sanskrit equivalent of Ālavāi—as one of Lord Shiva’s sacred sites on earth. But it includes Prabhāsa-kshetra and Hātakeshvara (of Pātāla) in its enumeration. Nonetheless, the text notes that some of these holy spots lie along the banks of the rivers Tāmraparnī and Vegavatī. Interestingly, the Vegavatī in the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM corresponds to the Vaigai in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM. Both Vaigai and Tāmraparnī are celebrated in ancient Tamil literature as the prominent rivers of the Pandya realm. It is noteworthy, however, that concerning the Sōmasundara Linga of Madurai in particular, both the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and the HĀLĀSYA MĀHĀTMYAM speak only of a vast pond or lake adorned with golden lotuses, making no mention of any river in its vicinity, while the SKANDA PURĀNA refers to a sacred water-body named Pātālagangā in connection with the Hātakeshvara of the netherworld.

The Ādaga-Madurai:

As inferred from the Skanda Purana, Hātakeshvara is a compound Sanskrit term derived from Hātaka (gold) and īshvara (supreme deity). Moreover, based on the contextual narratives within the text, it is conceivable that the term Hātakeshvara referred not only to the linga but also to the sacred site associated with it.

The Tamil equivalent of Hātaka is Ādagam. Notably, the Tamil hymn Pōtri Tiru-agaval (verse 90), composed by Saint Manikkavāchakar, eulogises Lord Shiva as the “Lord of Ādaga-Madurai“. Interestingly, according to the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM, Manikkavāchakar, before renouncing worldly life, had served as a minister to King Arimarthana Pāndyan in Madurai. Moreover, the remarkable resemblance between the story of Tadātagai in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and that of Ādaga-Soundary in the KŌNESAR KALVETTU SĀSANAM—compiled, edited, and annotated by Vaithyalinga Desikar—appears to further reflect the enduring concept of Ādaga-Madurai.

Thus, considering all the points discussed hitherto, I am inclined to conclude that the Madurai extolled in the TIRUVILAYĀDAL PURĀNAM and the Hātakeshvara of Prabhāsa-kshetra, glorified in the SKANDA PURĀNA, were regions that shared a profound cultural, political, and geographical affinity in the remote past.

The Continuing Connection:

The modern city of Madurai is in Tamil Nadu, whereas Prabhāsa-kshetra (Prabhās or Dev Patan) and Hatakeshvara (Vadnagar) of current times are in Gujarat. You may, therefore, wonder how these regions were territorially tied in ancient times. If so, I encourage you to refer to my earlier articles on the location of the Purānic Madurai, which—when viewed in conjunction with the insights presented here—also shed light on the probable location of the Purānic Prabhāsa-kshetra.

Interestingly, the sizeable Saurāshtrian community residing in Madurai appears to corroborate the traditional connection between Madurai and Prabhāsa-kshetra highlighted in this article. Furthermore, Nachinārkkiniyar, in his commentary on TOLKĀPPIYAM (Sirappu-Pāyiram and also Porulatikāram Verse No. 32), records that a considerable group of people—under the guidance of Sage Agastya—migrated southward from Dvārakā, the city founded by Lord Krishna. It is well known that Krishna, who belonged to the Yadu Dynasty—a prominent branch of the Lunar Dynasty—originally hailed from Mathurā. Conversely, the Tamils often refer to Mathurā as Vada Madurai—“Madurai of the North”—and to Madurai as Madurā-puri or Mathurā-puri. Traditionally, Lord Krishna’s Mathurā and Dvārakā are identified with the modern cities of Mathurā in Uttar Pradesh and Dvārakā in Gujarat, respectively. Moreover, according to the SKANDA PURĀNA, Lord Krishna, along with Balarāma and Subhadrā, worshipped Hātakeshvara and later chose to give up his mortal body at Prabhāsa-kshetra. The MAHĀBHĀRATA and the BHĀGAVATA PURĀNA likewise affirm that Krishna deliberately departed from the world at Prabhāsa. Thus, the sacred histories of Madurai, Prabhāsa, and Hātakeshvara appear to have been inextricably interwoven since time immemorial.

Closing Message:

You may now be wondering whether the Sōmasundara Linga of Madurai and the Sōmanātha Linga of Prabhasa-kshetra were, in fact, one and the same in the Purānic times. Intriguingly, certain subtle details preserved in scriptural accounts and traditional stories seem to hint at such a connection. However, I shall reserve the relevant evidence and discussion for a forthcoming sequel to this article.

End-Note:

Thanks for reading this post; please leave your feedback in the comment box below.

Check the Home page for the latest posts from our blog.

Browse the Blog page to find all the posts.

Visit the About page for an introduction to the blog.

Learn about the Research, Titbits, and Bliss sections of this blog.

To know the terms and conditions of this blog, please read the Norms page.

Click Contact to send me a message or to find me on social media.